With our Colorado house sold and free time opening up again, I’ve gone back to preparing print-on-demand editions of The Cunning Blood and Ten Gentle Opportunities. The layout part is done, and what remains is largely creating covers and cross-sell ads for my other books on the last few pages. While screwing around with the layout for The Cunning Blood, I remembered that the universe I built for it back in 1997 shared an idea with the first serious SF story I ever wrote, which I wrote just about precisely fifty years ago.

I’d written stories before that. In fact, I’m pretty sure I wrote a story about my stuffed dogs going to the Moon when I was 8. I tinkered with Tom Swift Jr pastiches after that, and made a couple of runs at “adult” SF without finishing any of them. But some time in April or May 1967, during the spring of my freshman year in high school, I finished an SF short story for the first time.

The story may still be in one of two boxes of manuscripts that I still have; I don’t know. Looking for it would be a bad use of my time. (I’ve wasted time looking for others that have gotten themselves lost somewhere along the way.) I remember it very clearly because it illustrates why I had trouble with characterization for many years afterward. Characters were not what interested me. I was into SF up to my eyebrows as a teen, but I was in it for the ideas. In fact, I learned to write SF by imitating idea-stories in MMPB collections that gathered the best of the SF pulps. A lot of that was Big Men with Screwdrivers, or in the case of George O. Smith, Men with Big Screwdrivers. That was fine by me; I liked screwdrivers. So when I started writing my own stories, the process went like this: I got an idea, and then spun a plot around it. The characters existed to serve the plot (in truth, I considered them part of the plot) and I freely borrowed character types from the growing pile of MMPBs I’d been buying with my allowance money since I started high school.

The story was called “A Straight Line Is the Shortest Distance.” Here’s the summary: In a very Trekkish galactic confederation, a crew of starship guys (mostly humanoid aliens) is tasked with testing a big new starship with a new species of hyperdrive promising unheard of superluminal speeds. The plan is to run the drive at top speed for an hour, just cruising in a straight line, to see how far they’d go. So they strap in, energize the drive, and run it for an hour…only to discover that they’re back where they started.

In a sense, it’s a What Just Happened? story. The rest of the tale is one of the alien crew members explaining that they had just proven that our three-dimensional universe lies in the surface of a (very large) four-dimensional hypersphere. In an hour, the starship Gryphon had held to a very straight line…and circumnavigated the cosmos.

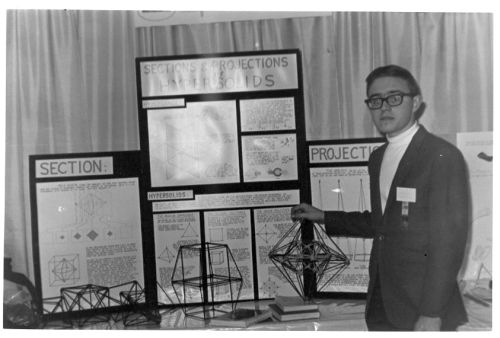

That’s it. No fights, no malfunctions, no mayhem or jeopardy of any kind. It was basically a geometry lesson. I was big into four dimensional geometry in high school (see photo above, of my senior year science fair project “Sections and Projections of Hypersolids”) so I thought it was a wicked cool idea. Then I showed it to the little girl down the street, who, like me, lived on SF and hammered it out on an old Olivetti mainframe typewriter. She liked the story, too. But what did she like the most about it? The aliens in the crew. The new starship and its wicked fast hyperdrive? Meh.

At the time, the lesson was lost on me, nerdball that I was. Eventually I figured out that hyperdrives just aren’t enough. It took a few years (decades?) but I got there.

The piece of “A Straight line Is the Shortest Distance” that survives in what I think of as the Metaspace Saga is the notion that our universe is the surface of a four-dimensional hypersphere. The interior of the hypersphere is something I call metaspace, a concept that I first presented in The Cunning Blood. The shape of the interface between our cosmos and metaspace is fractally wrinkly, and those wrinkles are significant. But more than that, metaspace is a computer. It’s an almighty big one, and it’s set up as a four-dimensional state machine that recalculates itself trillions of times per second. A 4D Game of Life grid, in essence, and it definitely contains life. (I mentioned that here a little while back.)

Sidenote: Several people have asked me if I will revisit the Sangruse Device, Version 10 in a sequel, and if so, explain what it’s up to. When we last left V10, it had absconded into the vastness between galaxies with an entire planet, intending to create a femtoscope a million kilometers in diameter. It will detect the Il, who inhabit metaspace, and communicate with them. At that point, the rowdier factions of the Il will again mess with V10. But this time, 10 will not take it lying down. Nope. Never one for measured response, the Sangruse Device will then invade metaspace. You want mayhem? Hold my wine.

Anyway. Over the last fifty years, I’m sure I’ve written half a million words of SF and fantasy, at least if you count the stuff still sitting in the shed in two beat-up moving boxes. Most of it was idea-rich and character poor (and on the whole, pretty dumb) but remember that I wrote much of it when I was a teen and (lacking a job or a girlfriend) had little else to do. It was good practice, and the ideas are all mine, free for the stealing. If I can avoid The Big Upload for another twenty years, you will see more than a few of them.

This is one reason I tell aspiring SF writers to retain their juvenalia and early efforts, even if they’re never published and no matter how dumb they may seem. Apart from reminding you how far you’ve come, you never know when one of the ideas you had in high school may suddenly pop up again and become useful, even fifty years later.

Stay the course. Keep writing. It’s an astonishing life to live!

Everyone reading this who did science fair projects, raise your hand!

And those who later became science fair judges, raise your other hand!

A lot of hands in the air, I suspect …

That’s what Robert Heinlein did with his first novel-length manuscript, For Us, The Living. He never published it during his lifetime, but he mined it for ideas that he used in a large number of published works. When the original manuscript was eventually found and published, fans could clearly see the connections.

Your description of metaspace sounds rather like we live inside of God’s brain.