It took a few minutes of flipping through some books in my workshop, but I eventually found what I remembered: That one of my “boys” books contained a description of a tabletop X-ray setup. The book in question is The Boy Electrician, the first volume of many from Alfred Morgan, who later wrote The Boys' First Book of Radio and Electronics and its three sequels, all of which loomed large in my tinkersome youth. The Boy Electrician was originally published in 1913 and is now in the public domain. The 1913 edition has been reprinted by Lindsay Books and I consider it worth having. There was a significant revision in 1943 that added chapters on radio and a few other things, and as best I can tell, the copyright on that edition was not renewed and it too is now in the public domain. A 40 MB PDF of the 1943 edition is here.

It took a few minutes of flipping through some books in my workshop, but I eventually found what I remembered: That one of my “boys” books contained a description of a tabletop X-ray setup. The book in question is The Boy Electrician, the first volume of many from Alfred Morgan, who later wrote The Boys' First Book of Radio and Electronics and its three sequels, all of which loomed large in my tinkersome youth. The Boy Electrician was originally published in 1913 and is now in the public domain. The 1913 edition has been reprinted by Lindsay Books and I consider it worth having. There was a significant revision in 1943 that added chapters on radio and a few other things, and as best I can tell, the copyright on that edition was not renewed and it too is now in the public domain. A 40 MB PDF of the 1943 edition is here.

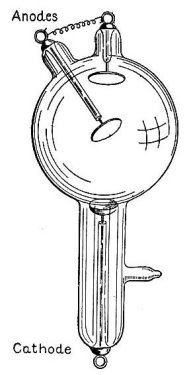

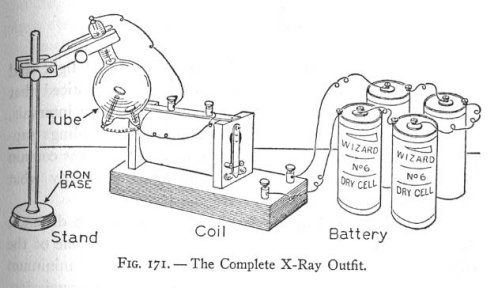

The Boy Electrician explains that “it is possible to obtain small X-ray tubes that will operate satisfactorily on an inch and one half spark coil.” This does not refer to the coil's dimensions; it means a coil capable of generating a spark an inch and a half long. He goes on to say that X-ray tubes cost about four and a half dollars each (albeit 1913 dollars) and may be obtained from laboratory supply houses. Hookup is fairly simple, with the spark coil driven by four of those wonderfully gutsy #6 dry cells with the huge carbon rod running down the middle. The drawing of the setup is shown below:

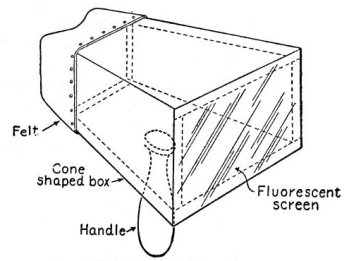

Morgan explains that you can either view images directly with a fluoroscope or expose ordinary photographic plates by placing an object to be X-rayed between the tube and the plate and leaving it there for fifteen minutes. This includes things like purses, mice, or…your hand. If you have the money, he also explains that a hand-held fluoroscope may be constructed by simply coating a sheet of white paper with crystals of platinum barium cyanide. It looks like the fluoroscope screen is used by basically staring at the X-ray tube with the object to be X-rayed between the tube and the paper screen.

Morgan explains that you can either view images directly with a fluoroscope or expose ordinary photographic plates by placing an object to be X-rayed between the tube and the plate and leaving it there for fifteen minutes. This includes things like purses, mice, or…your hand. If you have the money, he also explains that a hand-held fluoroscope may be constructed by simply coating a sheet of white paper with crystals of platinum barium cyanide. It looks like the fluoroscope screen is used by basically staring at the X-ray tube with the object to be X-rayed between the tube and the paper screen.

It would be interesting to know just how many boys bought the tube and tried to make it work; though given that $4.50 in 1913 would be about $100 today, I doubt it was many. Nor do I know how toxic platinum barium cyanide is, but I'm guessing a little more than iron filings. (On the other hand, my 1962 chemistry set contained a little bottle of sodium ferrocyanide, which sounds much worse than it actually is.)

It would be interesting to know just how many boys bought the tube and tried to make it work; though given that $4.50 in 1913 would be about $100 today, I doubt it was many. Nor do I know how toxic platinum barium cyanide is, but I'm guessing a little more than iron filings. (On the other hand, my 1962 chemistry set contained a little bottle of sodium ferrocyanide, which sounds much worse than it actually is.)

I remember taking The Boy Electrician out of the Chicago Public Library when I was 12 or so and pondering the X-ray project. What stopped me wasn't any fear of X-rays themselves, but concern that the whomping big spark coil would wipe out TV reception for a quarter mile in every direction and get me in trouble with the FCC. My friend Art had an old Model T ignition coil, and we could hear it sizzling on Art's transistor radio for half a block. The project had to be safe; I mean, the book was in the juvenile section of the library…

We knew less about a lot of things in 1913; X-rays were in some respects the least of it. But the hazard is significant, if not as bloodcurdling as luddites specializing in radiation insist. People used to self-treat insomnia by inhaling chloroform; well-known Victorian British scientist Edmund Gurney died by falling asleep with a chloroform-soaked cloth next to his nose. We know more now, and understand the precautions a great deal better, which has led to an escalation of conern that (untempered by any grasp of statistics or risk evaluation) quickly descends to rank superstition. One has to wonder how much knowledge isn't obtained these days simply because people are afraid of small but nonzero hazards. Panic over traces of phthalates—then heedlessly drive fifty miles to a football game with a car full of kids. It's the modern way of life.