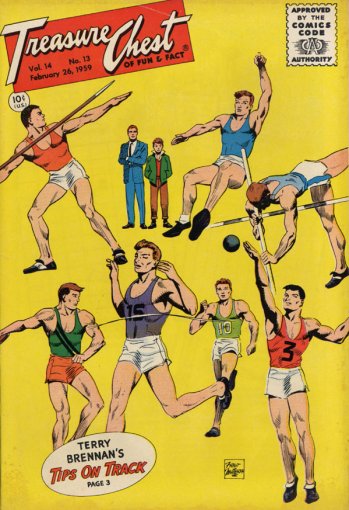

Even diehard comics fans have generally never heard of Treasure Chest of Fun and Fact—unless, of course, they went to Catholic grade school between 1946 and 1972. It was a comic book produced in Ohio for national distribution to parochial schools, and maps well to the era of Postwar Triumphal Catholicism. I was a grade schooler between 1958 and 1966, so Treasure Chest was always kicking around somewhere, along with Our Little Messenger, Young Catholic Messenger, and numerous other things that the George A. Pflaum Company of Dayton was always pumping out. I read Treasure Chest when it was handy, though I did so absent-mindedly and was never a big fan. The comic ran the gamut from preachy (always) to silly (often) and the quality was very uneven. The larger and long-running series were often beautifully done from a writing and art standpoint, though much of it glorified sports, which was a Catholic fetish at that time, in the hopes that young boys exhausted by sports will not go off by themselves somewhere and, well, you know.

Even diehard comics fans have generally never heard of Treasure Chest of Fun and Fact—unless, of course, they went to Catholic grade school between 1946 and 1972. It was a comic book produced in Ohio for national distribution to parochial schools, and maps well to the era of Postwar Triumphal Catholicism. I was a grade schooler between 1958 and 1966, so Treasure Chest was always kicking around somewhere, along with Our Little Messenger, Young Catholic Messenger, and numerous other things that the George A. Pflaum Company of Dayton was always pumping out. I read Treasure Chest when it was handy, though I did so absent-mindedly and was never a big fan. The comic ran the gamut from preachy (always) to silly (often) and the quality was very uneven. The larger and long-running series were often beautifully done from a writing and art standpoint, though much of it glorified sports, which was a Catholic fetish at that time, in the hopes that young boys exhausted by sports will not go off by themselves somewhere and, well, you know.

I was chasing memories around the Web the other night when I discovered the Treasure Chest archive at the Washington Research Library Consortium. This is a wonderful thing, but for copyright reasons it only has the magazines from 1946 through the end of 1963, which is unfortunate for reasons I'll relate shortly. I remembered only three of the continuing series; the rest of it had fled my brain cells until I started skimming the archive. There were textual letters from some priest (probably advising young boys not to go off by themselves somewhere and, well, you know), illustrated lives of the Saints, and insufferable lectures by Patsy Manners on etiquette and how to throw good parties. (Mixed parties! No, don't read that! We don't do such things in Chicago!) It was a real and sometimes classic comic; if you read nothing else, check out Kidnaped by a Spaceship from 1959. If they ran more like that I might have been an enthusiastic fan, but no; most of what we got was like Chuck White and His Friends, which was about an older guy who took young boys off on wholesome adventures, I'm sure so that they would not go off by themselves somewhere and, well, you know. Funny animals were big, and for a bit of prescient comic surrealism (I flashed on Cerebus) skim The Bear and the Wicked Wainwright. (At one point the Wainwright calls the Bear a “base poltroon,” which became faddish on the playground for a few weeks, though I may have been the only one of us sixth graders who bothered to look up “poltroon.”)

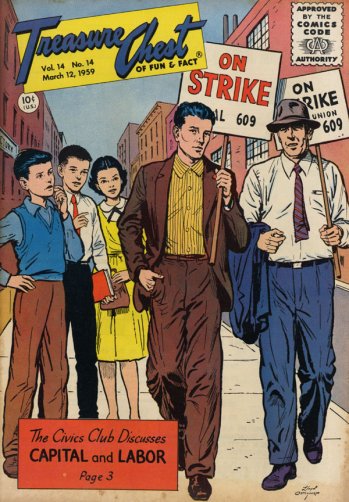

If Treasure Chest is currently famous for one thing, it was for the 1961-62 series This Godless Communism, which still gets the lefties het up. I rolled my eyes a little then and still do; the problem with Communism is not its godlessness but the fact that it murdered a hundred million people in the 20th century alone. Treasure Chest understood its working-class Catholic audience and was completely comfortable with praising organized labor in one of its illustrated civics lessons. No contradictions here; being a liberal has not always meant being a Marxist.

If Treasure Chest is currently famous for one thing, it was for the 1961-62 series This Godless Communism, which still gets the lefties het up. I rolled my eyes a little then and still do; the problem with Communism is not its godlessness but the fact that it murdered a hundred million people in the 20th century alone. Treasure Chest understood its working-class Catholic audience and was completely comfortable with praising organized labor in one of its illustrated civics lessons. No contradictions here; being a liberal has not always meant being a Marxist.

And Treasure Chest was fundamentally liberal, as the term was understood in its time. If it has been famous primarily for This Godless Communism, it may soon become even more famous for something else: a 1964 series called 1976: Pettigrew for President! inked by the well-known comics artist Joe Sinnott. Again, it was a multipart civics lesson: A very slightly futuristic tale of how a candidate runs for President during the election of 1976—12 years in our future—with a little political huggermugger thrown in to keep it from being completely boring. (There were a few scenes with the SST, but in truth not a lot of other futuremongering. I was disappointed. What? 1976? No flying cars?) What none of us noticed at the time is that we never actually saw Mr. Pettigrew full-on. We saw his back, his hands, and so on, but never got a good look at him. I guess we all figured that it was about the process and not the man himself, and in truth we were all taken in and completely poleaxed when on the final page it was revealed that Timothy Pettigrew was Black! He got the nomination, but beyond that the story was open-ended. Here's what the final panel said, courtesy NPR:

“And so this man Pettigrew became the first Negro candidate for the President of the United States. He then went out across the land, this black man, to campaign for the highest office. Would he win? Well, the year was 1976. It was the 200th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Could he win? Well, it would depend in part on how the boys and girls reading this comic grew up and voted … it would depend on whether they believed and, indeed, lived those words in the declaration — All Men are Created Equal.”

Alas, I have yet to see the comic scanned and posted anywhere, since content published in 1964 and after is automatically still in copyright. (The earlier issues had not been renewed and thus passed into the public domain.) The best we can do is a YouTube video, of all things.

It's a measure of our progress that what was seen as an inspiring piece of comic book science fiction in 1964 smacks of tokenism today: So we should vote for him just because he's black? Or dare we ask whether he has a chance of running the country? (The country may end up doing a lot of growing up next year, heh.) And if you ever wanted to invest in comic books, now's the time to hunt down and grab Treasure Chest Volume 19, issues 11-20. They're going to be worth something soon, no matter which way things go this fall.

[…] 1964 Treasure Chest comics series “Pettigrew for President” online, for free download. I blogged about this years ago, but the comic was not available for download […]