Whew. Took another 30-odd pounds of paper up 14 feet of stairs and out to the garage, and I’m catching my breath again. This is turning out to be weight training with a vengeance.

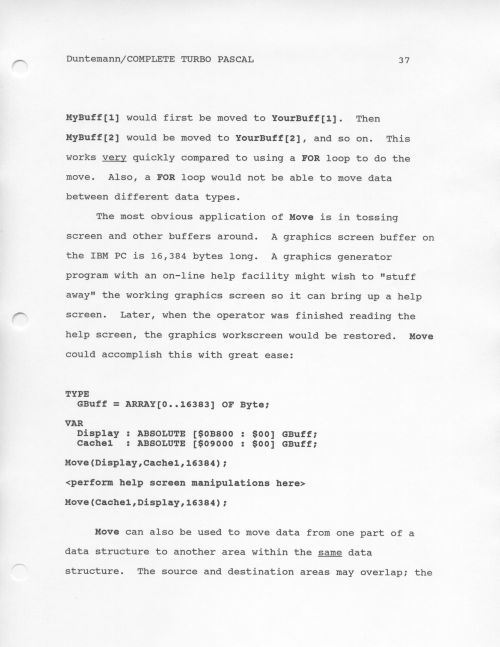

Anyway. Reader Vince asked (in the comments under my entry of April 14, 2016) if I could post a page from the manuscript of my 1986 book, Complete Turbo Pascal, Second Edition, which turned up while purging the collection in our furnace room. I chose a page at random just now, slapped it on the scanner, and there you go. It’s mostly readable, even at 500 pixels wide, because it was good-quality output from my first laser printer. The page number means nothing. Each chapter was its own file, with page numbers starting from 1.

Keep in mind that this was a book focused on the IBM PC and (egad) Z80 CP/M. In other words, this was a book about getting things done. I acknowledged the pure spirit of completely portable Pascal–and then dynamited it into the next county.

It’s interesting to me, as a writer, how the conventions for writing book-length nonfiction have changed in the last 30 years. When I wrote my chapters for Learning Computer Architecture with the Raspberry Pi two or three years ago, we agreed to work in a common word processor format (.docx) using comments, and applying paragraph and header styles to the text as we went. The chapters looked like printed book pages even while they were being written. Thirty years ago, we wrote in whatever word processor we wanted, and then sent a huge big pile of paper to the publisher. I don’t think I sent actual files to a publisher until the first edition of my assembly book in 1989–and I sent the files on 5″ floppy disks through the mail after sending that big pile of paper!

By the way, my Raspberry Pi book is still a live project, and I sent back my second chapter of six yesterday after author review of copyedits. Beyond that, I can’t tell you much, especially when I think it might actually hit print.

Ahh. Breathing normally again. Time to lug another boxful out to the garage.

Thanks Jeff! That code surely brings back memories.

Off the top of your head, how long did it take for the publisher to typeset a manuscript of that size, during those years?

The answer? For-freaking-EVER. They had human typists type it all in, and then I had to go through galleys, (which were strips of typeset text from a phototypesetter) and finally page proofs once they laid it out. The first edition (which appeared in the summer of 1985) took so long to produce that Doug Stivison’s book on Turbo Pascal beat me to market, even though I’m pretty sure I had the first one finished. I think it was a full six months and change from the time I mailed them the manuscript to the time the book was on press. At Coriolis we used to turn them around in a month.

There was no email, though I believe I got MCI Mail sometime during 1985, courtesy my employer, Ziff-Davis. (The Internet was not yet open for general use.) Everything was done via phone and FedX.

I enjoyed being young, but damn, I enjoy today’s tech probably more. One wonders what that says about me…

But ho long did it take fir. TAB book to prepare for publication?

That was the hobby electronic publisher which was second rate, often low definition or low contrast photos, and no attempt t keeping the graphics with the relevant text. Thy had their share of errors too, I gather.

The classic commentary was when a columnist in Popular Electronics warned the readership not to buy his book about the 6809. He had ä list of errors, but seemed especially upset that they had taken out the chapter with the listing for a 6809 tiny BASIC, but did leave in the chapter about using it, kind of useless without the code.

Michael

Jeff, I’ve been reading your blog on and off for at least 15 years. I can’t recall you ever writing about entrepreneurship, or providing advice for anyone thinking about running a business (have you?). I’m pretty sure you’d have valuable insights. Keen to read some of your reflections on being a successful businessman and your practical advice in a future post.