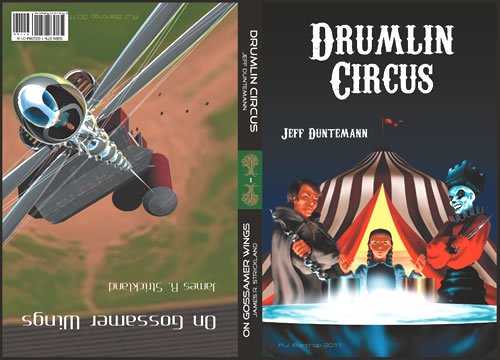

For the last several days I’ve been tinkering with my collection Cold Hands and Other Stories to get it ready for sale as an ebook. The book is now available in epub format on the B&N Nook store ($2.99; no DRM) and should appear in mobi format on Kindle in the next day or so. All of my shorter Drumlins stories are in that book, so if you liked Drumlin Circus and On Gossamer Wings, do please consider it.

Print is a more interesting issue. Cold Hands has been available as a printed paperback on Lulu for some time now, but I haven’t been satisfied with the book’s visibility, especially on Amazon. Lulu is certainly the easiest of all the POD services to learn and use, but to sell books you have to drive customers to the Lulu site, and they have to buy through the Lulu shopping cart. That’s a huge drawback, especially for fiction, where the per-sale earnings are low and you’re not targeting the books at an easily reachable audience; i.e., if you’re not a big name in SF. Also, many people won’t buy a book unless it can be had through Amazon, because online account proliferation is an issue for them. (I understand that hesitation completely.)

I’ve done well with my Carl & Jerry reprint books on Lulu for several years now because people go looking for Carl & Jerry. The audience knows the stories, many having read them in the 1960s. I have a substantial index page, and the page is the top search hit whenever anybody searches for “Carl and Jerry.” My two books on Old Catholic history are almost cult favorites by now, and I sell a couple of copies per month on Lulu without even a detailed summary page. (I do have descriptions on the Lulu storefront.) They sell when people talk about them in the many Old Catholic email groups, which is far oftener than I would have thought. I mention them in a post now and then, and the books keep selling. Word of mouth works well within close-knit enthusiast groups like that who understand what the books are about.

Breaking in to SF is harder. To sell paperback books of my SF I simply have to be on Amazon. That’s Lulu’s #1 issue. My Lulu books are sometimes listed and sometimes not, for reasons I don’t really understand. A search just now for Cold Hands and Other Stories does not show the book, and that’s unacceptable.

So I’ve been giving CreateSpace a look. It’s Amazon’s in-house POD service, and was originally called BookSurge before Amazon broadened it to embrace other kinds of content, like music CDs. I can use my own ISBNs there, and if you publish on CreateSpace, you will be listed on Amazon.

CreateSpace is more complex to use than Lulu, though it has nothing on Lightning Source. If you’re serious about publishing your material and expect to sell more than four or five copies it’s worth studying. The economics are better, and I’ll close out this entry with a quick summary.

First, Lulu: Cold Hands and Other Stories has a cover price of $11.99. Lulu’s per-copy manufacturing cost for the book (232 pages) is $9.14. Lulu’s commission is 57c, leaving my per-sale take as $2.28. That’s as complex as it gets over there.

CreateSpace has a more complex pricing system, and the easiest thing for me to do is just copy out a screenshot of the royalty calculator for Cold Hands:

They don’t state a fixed unit manufacturing cost, but they tell you how much you’ll make in the various retail channels. The “Pro” option here is a $39, one-time-per-title cost that has to be earned out before you see any profit. (I think of it as a processing fee for the title, while allowing CreateSpace to compete with Lulu on the “free to post” issue. There’s no charge to mount a book, if you’ll take less per copy.) For Cold Hands that would be about twelve copies, depending on the channel mix. The eStore figures are for sales through CreateSpace’s online system. The Expanded Distribution option is for sales made through other online retailers and independent print booksellers. Obviously, if you’re going to drive sales, it pays to drive them to the CreateSpace eStore rather than simply referring them to Amazon.

I had originally intended to mount Cold Hands on Lightning Source, but I wanted to get some real-world experience with CreateSpace. It’s not up there yet (their review process takes a couple of days) but should be there by early next week.

The missing link, of course, is a Web page to drive sales to CreateSpace, and I’m working on that. More as it happens.

And triggers, yeah. One of the most popular events at Anomaly was a do-it-yourself maker session for building steampunk ray guns. Pete Albrecht sent me a note about a whole category of real-world firearms that has a certain steampunk whiff about it:

And triggers, yeah. One of the most popular events at Anomaly was a do-it-yourself maker session for building steampunk ray guns. Pete Albrecht sent me a note about a whole category of real-world firearms that has a certain steampunk whiff about it: