- My old friend and fellow early GTer Rod Smith has posted a great many excellent pictures he took at Chicon 7, including a book signing that I attended.

- My mother’s cat Fuzzbucket died yesterday, at 16 years and change. He outlived my poor mother by twelve years, and while skittish as a kitten eventually warmed to me. I’ve never had a cat (for obvious reasons, of which I have four right now) but of all the cats I’ve never had, Fuzzbucket was my favorite. He kept his own LiveJournal page, and the final entry brought a tear to my eye.

- For those who couldn’t attend Chicon and were cut off from viewing the Hugo Awards by an idiotic copyright protection bot, you’ve got another chance: The award ceremony will be re-streamed tomorrow night, September 9, at 7 PM central time.

- This morning’s Gazette had an ad for hearing aids, which bragged of their product having 16 million transistors. This is easier than it used to be, since all those transistors are in one container. Now, does anybody remember the days when ads bragged of radios containing six transistors?

- And while we grayhairs and nohairs are recalling transistor counts in the high single digits, does anybody remember the early Sixties scandal (reported in Popular Electronics, I think) in which Japanese manufacturers would solder additional transistors into simple superhet boards and short the leads together, just so they could advertise the box as a “ten-transistor” radio?

- Nice piece from Ars Technica on the deep history of the spaceplane.

- Bill Cherepy sent a link to a marvelous steampunk tennis ball launcher, used for getting pull-strings for antennas (and as often as not, the antennas themselves) into high or otherwise inaccessible places. Gadgets like this (albeit not in steampunk dress) have been around for a long time, and I posted a link to this one (courtesy Jim Strickland) back in March.

- Also from Bill (and several others in the past few days) comes word of a promising if slightly Quixotic attempt to preserve orphaned SF and fantasy. Here’s the main site. At least they’re offering money to authors and estates; most other preservation efforts (of pulp mags and old vinyl, particularly) are pirate projects most visible on Usenet.

- That said, there are projects that limit themselves to out-of-copyright pulps, like this one. One problem, of course, is knowing when a pulp (or anything else from the 1923-1963 era) is out of copyright. Copyright ambiguity only hurts the idea of copyright. We need to codify copyright and require registration, at least for printed works. I’m not as concerned about copyright’s time period, as long as the owners of a copyright are known. As I’ve said here before, I’m apprehensive about competing with hundreds of thousands of now-orphaned books and stories.

- I don’t eat much sugar anymore, but egad, there are now candy-corn flavored Oreos.

books

Odd Lots

Worldcon Wrapup

It was a relief to step off the plane in Colorado Springs and grab a chestful of thin, dry air. I’ve lived in dry climates since early 1987, and I’ve lost my taste for late-summer Chicago mugginess. The toughest part of Chicon 7, which concluded on Monday, was going back and forth across the Chicago River between the Hyatt and the Sheraton and wondering if I were walking above the river or wading through it. The con went very well, considering my aversion to crowds. I got to see a lot of people I don’t see very much, granted that I missed a few. I heard some readings and workshopped a couple of stories with my friends from the 2011 Taos Toolbox workshop. And the Hugos, which I haven’t seen in person since (I think) 1986. John Scalzi was easily the best Hugos toastmaster I’ve seen since I began attending worldcons in 1974. He was funny, he was terse, he was great at improv, and he held the awards for the winners as they spoke their thank-yous into the mic. (There was nowhere else to put them.) He’s losing his hair and doesn’t shave his head–he certainly gets private points from me for that.

It was a relief to step off the plane in Colorado Springs and grab a chestful of thin, dry air. I’ve lived in dry climates since early 1987, and I’ve lost my taste for late-summer Chicago mugginess. The toughest part of Chicon 7, which concluded on Monday, was going back and forth across the Chicago River between the Hyatt and the Sheraton and wondering if I were walking above the river or wading through it. The con went very well, considering my aversion to crowds. I got to see a lot of people I don’t see very much, granted that I missed a few. I heard some readings and workshopped a couple of stories with my friends from the 2011 Taos Toolbox workshop. And the Hugos, which I haven’t seen in person since (I think) 1986. John Scalzi was easily the best Hugos toastmaster I’ve seen since I began attending worldcons in 1974. He was funny, he was terse, he was great at improv, and he held the awards for the winners as they spoke their thank-yous into the mic. (There was nowhere else to put them.) He’s losing his hair and doesn’t shave his head–he certainly gets private points from me for that.

I was not aware of it at the time, obviously, but a misguided attempt at automated copyright protection killed the stream that Chicon was sending out to people who couldn’t be at the con. This was idiotic on so many levels–the video clips being “protected” had been given to the con by the studios specifically to be shown at the awards–and reminds us that robots should not be enforcers. Never.

The very idea of copyright, on which artists in many areas depend, is being weakened in the public mind by crap like this. If something eventually kills copyright, it won’t be the pirates.

I had a marvelous interview with the fiction editor at a major press, at which he agreed to read the manuscript for Ten Gentle Opportunities. Better than that, he took notes on my experience and my background (I brought both The Cunning Blood and one of my computer books) and suggested that what he might like even more from me than a humorous fantasy mashup was a good ripping hard SF action adventure.

I wondered for a moment: Gosh, could I do that? (Only a moment. A short moment. Ok, no moment at all.) I had intended to pursue my first Drumlins novel The Everything Machine after TGO was on its way. Now, I’m not so sure. The Molten Flesh is less far along, but it may get promoted to the top of the queue. We’ll see.

I did spend a fair bit of time with my sister and her girls down in the dealers room. (She and Bill publish and sell filk CDs as Dodeka Records.) As usual, I did a little shopping, emphasis on little. (We didn’t drive, so whatever I bought had to be packed home on what I call a “sewer-pipe jet.”) But I found something wonderful, as Dave Bowman notably said in 2010.

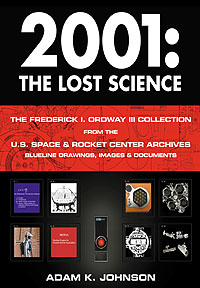

Across the aisle from Dodeka Records was Apogee Prime, a publisher specializing in aerospace books in several categories. They had a new book that, at 12″ X 14.5″, was mighty big for my creaky old suitcase, but I bought it anyway: 2001: The Lost Science. What we’ve got here are original photos, sketches, and literal blueprints of the technologies presented by Stanley Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Much of the material was thought to be lost, and when the sequel 2010 was filmed in the early 1980s, a lot of it had to be re-created from scratch, often by having artists watch the original movie fifty times with sketchpads in their laps.

The book draws on the personal collection of Frederick I. Ordway III, who is a real rocket scientist and former colleague of Werner Von Braun, and worked on the Explorer 1 project. Kubrick hired Ordway to help him predict, as reasonably and realistically as possible, what space science would be like in the year 2001. This book is a good overview of his predictions, at least those that made it into the 1968 film. Satellites, space stations, nuclear propulsion systems–these were the aches that a certain class of nerdy 16-year-olds were feeling in 1968. For a good many reasons, only some of which I’ve discussed here, 2001 has long been and will likely remain my favorite film of all time. I remember those aches, and wear them proudly, as they are the aches of boys who dare to dream.

This is a coffee table book, but one that you may actually read cover-to-cover. (I’m not quite done but will be soon. There have been times when I’ve had to take a deep breath and set it down.) Softcover. $49. Very highly recommended.

Algorithmic Prices on Amazon

I’m trying to write 38,000 more words on Ten Gentle Opportunities (basically, the rest of it) by Worldcon, so I won’t go on at length about this, but today I stumbled on some information on a topic I mentioned briefly several years ago: The weird way used book prices wobbulate around on Amazon. As it happens, the goofuses are apparently using software originally developed for high-speed stock trading. Techdirt explained the process in a little more detail last year, providing us (finally) a clue as to how a mild-mannered book on the genetics of certain flies could come to command the super price of $23,698,655.93. Lots more out there if you’re interested.

In short: If you define your book’s price as 1.270589 times that of your competitor’s, and your competitor defines his price as 1.270589 times yours, well, you’ll both be rich in no time…or at least pricing your books as though you were. Fly genetics never had it so good.

What remains a bit of a mystery is why you’d want to price your books above your competitor’s and not below. Unless…the game is to buy the book from your competitor when you find a buyer so dumb as to buy the book from you, at 1.270589 times the price they could get it elsewhere. It’s likely that the fly genetics book was not in either seller’s hands at any point.

Such clueless buyers may exist–after all, people are still installing smileys and comet cursors and anything else on the Internet labeled “free.” This implies that the magic number 1.270589 is in fact the atomic weight of Sleazium, which absorbs certain subatomic particles, particularly morons, better than anything else ever discovered.

The Agency Model and the Fair Trade Laws

All the recent commotion over the agency model vs the wholesale model in ebook retailing reminded me of something: my very first pocket calculator. I got my first full-time job in September of 1974, and whereas fixing Xerox machines wasn’t riches, it paid me more than washing dishes at the local hospital. In short order I got my first credit card, my first new car, and a number of other things that had been waiting for my wallet to fatten up a little.

One of these was a pocket calculator. The device itself has been gone for decades, but I’m pretty sure it was a TI SR-50, with an SRP of $149.95. I shopped around for the best price, since $150 was a lot of money back then. However, everybody who sold the SR-50 was selling it for $149.95. I bought it at a camera store downtown, and only a little research told me that it was covered under the Fair Trade laws, meaning that all retailers sold it for the same price, set by the manufacturer. I grumbled a little, but wow! I had a calculator! I gave it no further thought.

Between 1931 and 1975, a significant chunk of retailing in the United States was basically on the agency model. Books, cameras, appliances, some foods, wine and liquors, and certain other things were sold for the price the manufacturer chose. This is one reason prices were often printed right on the goods. Retailer margins were open to discussion, but in a lot of industries, the margin was 40% or pretty close to it. The Fair Trade laws were enacted during the Depression to protect local one-off retailers from being driven out of business by much larger chain stores, during a time of reduced demand and thin profits. How well this worked is disputed, but by 1975 the laws had become so unpopular with the public and so difficult to enforce that they were repealed by an act of Congress.

I grant that Fair Trade was not a clear win for the little guys. Some of my readings suggest that the Fair Trade laws accelerated the dominance of retail chains because chain retailers could build bigger stores and shelve a greater variety of goods, even if their prices were the same as prices in smaller, one-off stores. House brands were invented largely to evade the Fair Trade laws, since the retailer was considered the manufacturer for legal purposes and could set prices in stores as desired. This gave another advantage to large chains, since only large chains had the resources to establish house brands.

Fair Trade retailing as I understand it rested on two big assumptions:

- Manufacturers compete on price.

- Retailers compete on things like customer service and selection.

Shazam! Those are the same two assumptions underlying the agency model in publishing, and I don’t think it matters whether we’re talking print or digital. So I think it’s fair to look at what happened after 1975, when Fair Trade went away:

- Discounting allowed consumer prices to go down.

- Both the chains as a whole and individual chain retail stores got bigger.

- Smaller, independent stores vanished in droves.

- Small retailing became specialty retailing. This was certainly true of bookstores. Of the two bookstores I could easily reach on my bike in the 1960s, one became a card shop that carried a few books, and the other became a specialty bookstore carrying Christian/Catholic books only.

- Small retailers dealing in used goods hung on longer–think used bookstores and used record stores. The Doctrine of First Sale allowed used goods retailers to set their own prices even on Fair Trade goods.

- Manufacturer consolidation went into high gear. One reason, I think, was monopsony, which is the power big retailers have to dictate prices to suppliers. Smaller manufacturers who could not meet retailer price expectations merged with larger manufacturers, became importers, or went under.

In the ebook publishing/retailing world, #5 does not apply, as there’s no unambiguously legal used market. Most of the other consequences in the list above are things that I predict an agency model would work against:

- Retail prices will rise–though perhaps not as much as some fear.

- It will be easier to mount and maintain a new online retailer against competition by enormous retailers like Amazon.

- Given the above, with the consequence of more players in the retail market, monopsonistic pressures on cover prices will be greatly reduced.

- Absent Amazon’s monopsony, smaller publishers have a better chance of competing with much larger publishers, given small publishers’ advantages of lower fixed costs vs larger publishers.

- The presence of a larger number of smaller publishers will keep downward pressure on prices, since that’s their primary way to compete. Macmillan has to keep ebook prices up to protect its print hardcover line. Ten thousand small ebook publishers have no hardcover lines to protect. $10? No problem. $5? The new $10. Even within the agency model, small press will train consumers to expect ebooks to sell for $10 or less.

There’s another consequence that I don’t think has any precedent in the Fair Trade phenomenon: Larger numbers of retailers and publishers will reduce the power of very large retailers or publishers to “silo” the business with proprietary file standards and DRM.

There are problems with such an agency-based business model (and wildcards; Pottermore, anybody?) but overall I think those problems are more solvable than the collapse of book retailing into Amazon, Amazon, and more Amazon. So my vote goes with agency retailing. I’ve just told you why. (Polite) discussion always welcome.

Odd Lots

- Not posting often here, but I’m ok. Working hard on several things, chief of which is getting my office and Carol’s exchanged, outfitted, and fully functional. This involves furniture, wiring, lighting, and sorting an immense quantity of glarble. I hope to return to regular in-depth posting soon.

- I have a new favorite cheese: cave-aged gruyere, which can be had sometimes at King Soopers, and is lucious with a good dry red wine. Get the oldest cheese you can find, as young gruyere tastes nothing like old gruyere. A year is as young as I buy.

- The asteroid that whacked the dinosaurs must have thrown an immense amount of material into space. How much rock might have made the journey, and how far far did it go? Here’s a good quick take on the topic. It would take a million years or more to get to Gliese 581, but suitably rugged bacterial spores might have survived, and made the origin of life on planets there unnecessary. (Thanks to Pete Albrecht for the link.)

- A book I’m not bullish on: Steven Johnson’s The Ghost Map, which describes how the cause of cholera (infected water) was proven by the persistent John Snow through charting of cholera deaths upon a map of London neighborhood water pumps. Why? The book does not include the actual ghost map named in the title. (So what else is missing or wrong?) Whatever editor let that past should be fired and spend the rest of his/her days stuffing toddler clothes in racks at Wal Mart.

- Could the TRS-80 Mod 100 possibly be 30 years old? Yes indeedy, and it was ubiquitous among tech journalists when I was at PC Tech Journal in ’85-86. Its keycaps made a distinctive sound, and sitting in a significant press conference back then was like sitting under a tin roof in a rainstorm. I yearned for one myself (the keyboard was wonderful for such a small device) but didn’t pull the trigger because the machine did so little other than keystroke capture.

- Toward the end of my tenure at Xerox I saw the Sunrise, which was a more ambitious take on the “lapslab” concept. My department was considering writing an app for it, so I had a loaner for awhile. Even better keyboard than the TRS 100, cassette data storage, modem…but the 3-line display was harder to read. Xerox private-labeled the hardware from another company, and basically killed it with a $1500 price point. (There was a flashier version that cost…$2500!) Xerox abandoned the market in 1984, after sinking what rumor held to be an obscene amount of money into it.

- One machine I did consider was the Exidy Sorcerer, which also had a good keyboard and didn’t cost $3000. Lack of software made me spend the $3000 anyway, on a huge honking S100 system running a 1 MHz 8080.

- One of the big issues between Amazon and the Big Six is an explosion of co-op fees, which according to some reports have increased by 30 times since 2011. The whole “co-op” business has always smelled gamey to me, but it had a purpose in the B&M bookselling world. How it fits into online ebook retailing is less clear, and in my view starts leaning perilously in the direction of bribery.

- Most of us think that reading is in decline. Gallup poll results suggest otherwise. Nor are today’s books worse than those of 40+ years ago. This quote is significant: “The bad [books] of yesteryear have gone out of print while the bad ones of today are alive and being sold in supermarkets.”

- I’m still watching the ASUS Tranformer Prime (their botch of its GPS support has kept me away for the time being) but the Prime has a little (as in cheaper) brother now, and it looks like a decent machine in its own right. Here’s Engadget’s detailed review of theTransformer Pad TF-300.

- Here’s another wonderful gallery from Dark Roasted Blend, this time of high-speed photos of liquids. Some of it is photoshopped, but it’s all startling. (Thanks to Ernie Marek for the link.)

- Santorini is smouldering again. Yes, the volcano that may have made the Minoans extinct and launched the legend of Atlantis (or at least put an older legend on the map) is getting restless. Like the Greeks need that right now.

- Eating meat allowed our hominid ancestors to reproduce more quickly, by accelerating infant brain growth and thus shortening the breastfeeding period. (Breastfeeding naturally inhibits ovulation.) This on top of several other issues.

- From the Words-I-Didn’t-Know-Until-Yesterday Department: Beatboxing , which is vocal generation of sounds like drums and synthesized sound effects. I heard of this in an interesting way: There’s a slightly silly commercial for the Honda Pilot that involves a Pilot full of bored tweens beatboxing the rhythm of Ozzy Osbourne’s “Crazy Train,” and by chance we had captioning turned on. When the kids started making noises, the captioning read, “Beatboxing.”

- Pete Albrecht sends a link to a map color-coding US gas prices by county. The very abrupt differences between states suggests that gas prices are more a question of state and local taxes than regional differences in demand.

- It was inevitable: A 3D printer that prints chocolate novelties. Now we need a 3D printer that prints spice-cake Easter lambs with ears that stay on.

Invading the Most Favored Ebook Nation

Reports are pouring in this morning that the Department of Justice is preparing antitrust action against the Big Five publishers (Simon & Schuster, Hachette, Penguin, Macmillan, and Harper Collins) and Apple for conspiring to raise ebooks prices. (It’s a little ironic that I read it in today’s print Wall Street Journal, which I generally read before turning this damned thing on.)

The problem is in part the agency model, which allows publishers to set a price for books, and give retailers like Apple and Amazon a cut. Publishers are afraid of ebooks eating their hardcover lines, of course, but were absolutely terrified that Amazon’s loss-leader pricing of bestsellers at $9.99 would train customers to think that ebooks were worth $10 and no more. Publishers have experimented with windowed release, which holds back the ebook edition until the hardcover has a chance to generate its bigger bucks, but as best I know that’s not widely done. Agency pricing, however, has stuck.

Here’s an agency example, of a hardcover I read recently: Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature has a cover price of $40. (Publishing seems to be responding to the recent shortage of ‘9’ digits by rolling prices up a penny, at least on hardcovers.) All of the ebook stores that I’ve checked are selling the ebook version for $19.99. In an agency arrangement, publishers set both prices. The sales agent (that is, the retailer) gets 30% of the set price. In this case, that would be $6. The publisher gets the rest, here $14.

Why 30%? It’s arbitrary, and simply the number that Apple gave publishers when it changed its bookstore from the wholesale model to the agency model. Apple’s retail contract had a twist, which is really what’s getting them into trouble today: The “most-favored-nation” (MFN) clause, which specifies that publishers may not give other retailers better terms than they gave Apple. Much byzantine legal reasoning online, but here’s a short summary.

TGIANAL, but this still puzzles me a little, and I think we’ll learn more in coming days. MFN clauses have been litigated and are not themselves illegal. The sense is that, if anything, they tend to drive prices down. The current legal action from Justice seems to turn on whether the Big Five colluded on agency pricing (with Apple’s help) to force Amazon to accept the same terms that Apple got. The idea is that the parties named in the suit intended their actions to raise prices, a use of MFN that is in fact illegal. If that sounds like a hard thing to prove (rather than just allege) well, duhh.

As I’ve said earlier, I favor agency pricing, because it allows small, very small, and microscopic publishers to undercut the Big Five in a major way and maybe eke out a marginal living. You can bet that you won’t see 99c ebooks from Macmillan. Much of my puzzlement arises in wondering to what extent ebook publishing will be affected by things like the Robinson-Patman Act, which was created to prevent predatory pricing, though is not widely enforced these days. When the retailer’s role in selling ebooks is basically database management (or when the retailer becomes the publisher or even the author) predatory pricing is not an issue–but odder things have happened in the legal world before.

As always with complex legal issues involving enormous players with cavernous pockets, almost anything could happen. I think the case will either be settled before going to court, or else will be decided narrowly. Publishers may be stripped of their ability to demand that retailers accept the agency model, or any given given agency percentage. I think Amazon would love to retain agency pricing, and just negotiate a lower number.

As I’ve said many times: We’re still in the Cambian era of ebooks (the Pre-Cambrian Era ended with the arrival of the Kindle) and there’s still a whole mess of evolving to do.

Indies and Gatekeepers

Janet Perlman put me on to this article about why indie publishers (a category that may or may not include self publishers, depending on whom you talk to) get no respect. The whole piece might be summed up this way:

- Quality is hard work.

- Quality is expensive.

- Quantity is no substitute for quality.

I agree, as far as it goes. But that’s not the whole story. You can break a sweat and write a superb novel at considerable expense of time and energy. You can pay an editor to look at it and perhaps fix certain things. You can pay an artist for a great cover. You can pay somebody to do a great page layout, generate print images, ebook files, and so on. Having shelled out all that expense in time, money, and personal energy, you are not likely to sell many books or become especially well-known. Publishing is an unfair business in a lot of ways.

Perhaps the most unfair thing about publishing as we know it now is that it cares not a whit about quality. Sure, the publishers will tell you otherwise. So will the agents, and so will the retailers, assuming you can find any these days. Alas, it’s not true. Publishers, agents, and retailers are indeed our gatekeepers, and the gates are tightly kept. The gates do not open for quality, alas. The gates open in the hope of making money.

This is true not only in quirky markets like fiction (more on which in a moment) but in technical publishing as well. I’ve received and rejected beautifully written books that were well-organized and basically error-free, for a simple reason: The Radish programming language (I just made that up) is used by 117 people world-wide, which means the total worldwide market for a book about Radish is 116. (The author already has a copy.) On the flipside, the best possible book on Windows XP won’t be accepted at any traditional publishing house, because all the books on XP that the universe needs were written a long time ago.

The reverse is also true, to some extent. If a publisher thinks your book will make money, the book will probably be published. Being well-written doesn’t change this equation much. Back in the Coriolis era I spent a lot of money on developmental editors to make a manuscript readable in those cases where I suspected (after market analysis) that the book met a hitherto unmet need. I wasn’t always right, of course, but the point is that I didn’t accept or reject books based on any judgment of quality. What I was looking for was market demand.

This is true of fiction as well, in spades. I picked up Cherie Priest’s steampunk entry Dreadnought last year, and had to force myself to finish it. Two other people in my circle, who live 1,000 miles apart and don’t know one another, both described the book in a single word: Unreadable. (Another said the same of her earlier book, Boneshaker.) Dreadnought was dull, slow, short on ideas, over-descriptive in some places and far too sparse in others. Yet Cherie’s got a following and is evidently doing very well. Somebody at Tor thought her books would make money and took a chance. They were right. That doesn’t make them well-written. (I did like the covers, and covers do matter–if you can get them in front of the readers somehow.)

I don’t want to be seen as picking on Cherie, who will doubtless chew me out if she reads this. It’s a pretty common thing. Nor is it a new thing. Decades ago I read a lot of abominable novels, from Sacred Locomotive Flies to Garbage World. They got into the stores. They probably made their authors at least a little money. (They got mine, after all.) They were crap.

If Dreadnought made money, why would a book that was better written not make money? It’s a long list. The author may not have been able to get a hearing from the gatekeepers in the first place. Luck is needed here, as well as brute persistence, not that persistence is any guarantee. The topic may be considered out of style, or just worked out and already done to death. It may be too long. (I ran into this trouble with The Cunning Blood. Unit manufacturing cost matters.) The book may have been judged to push buttons in the public mind that the publisher would prefer not to push. (Back when I was in high school I read a purely textual porn comedy novel that was brilliantly written and hilarious. Would I publish it? Not on your life.) Books that demean women or minorities a little too much, or focus on cruelty to animals (or probably a number of other things) won’t be picked up as easily, and it has nothing to do with quality. It’s tough to make money in publishing, and publishers are trolling for as broad a market as possible.

This is why I think the article on HuffPo cited above is misleading. Quality is a problem, but not as much of a problem as the author thinks, and not in the same ways. Worse, solving the quality problem won’t make an indie publisher’s books any more likely to get into B&N, and suggesting to indie publishers that they will is just dishonest.

So what’s the answer? Don’t know. There may not be one. The publishing industry is in the process of changing state, and nobody knows what we’ll inherit in five or ten years. Losing B&N (or waking up one day to find that B&N is a tenth the size it was yesterday) could work to indie publishing’s advantage, at least if independent bookstores fill the subsequent vacuum. The more gates to the retail channel there are, the more likely it is that one will open when you buzz. Self-published ebooks have worked for people like Amanda Hocking with Herculean energy who write for twelve hours and then promote themselves the other twelve. Tonnage can get you noticed, even if it’s bad tonnage.

For the rest of us, again, I don’t know. Quality in all writing (fiction especially) is not the choke point. It’s an unfair and beneath it all a mysterious business. Submit good work if you can, but be prepared to have the gates shut in your face a lot. That’s just what gates do.

Odd Lots

- Of all the essential elements of science, proving causation is by far the hardest. Correlation only points in a direction that further research should take; it has no value in and of itself. (The title of the article is very hokey, by the way: Science is not failing us. Human ignorance–and corruption–are interfering with the scientific process.)

- Marvelously wrought steampunk playing cards. (Thanks to Bill Cherepy for the link.)

- I went to high school with one of these guys. (Joe Lill.) Very impressive piece of work. (Thanks to Pete Albrecht–another high school colleague–for the link.)

- I got one of these for Christmas from Lee Hart. We’ll soon see if I can still write COSMAC binary machine code in my head, 35 years later. F8 FF A2…

- Carol presented me with Steven Pinker’s new book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, and I will report after I finish it. Pinker’s stuff is always worth reading, and I’ve been waiting for this one for a long time.

- The Ropers (my sister Gretchen, Bill, and her girls) gave me one of these for Christmas, and having tested it on a few Meccano parts downstairs, I suspect it may turn out to be the best hex nut starter I’ve ever had.

- This is the first waterproof (more or less) tablet I’ve ever seen, and in my preferred 4:3 format to boot. And a MicroSD slot for sideloading! Details are still sparse, but it’s the first CES 2012 announcement that hasn’t made me yawn.

- I bought a Nook Color last week; more in upcoming posts. I heard today that you can now get a Nook Color for $99 or a Nook Simple Touch for free with a one-year subscription to the New York Times or People. I don’t know if this is good for the industry or not, but it may well do wonderful things for the Nook’s market share.

- There are challenges to living in the best Effin town in Ireland. (But nothing like those of a certain town in Austria.) Thanks to G. McDavid for the link.

- I offer this interesting piece as a glimpse into my ongoing research into the drivers of climate. I have long intuited that climate is a chaotic system, and we see evidence of two states in recent geological history. What the attractors are, and whether there are other states are questions of enormous importance, as is the question of how bad a change to the other known state would be. Note well: My tolerance of Climate Madness is now close to zero. Please limit comments to the points made in the article. If you wander into politics or comment angrily your posts will be deleted without hesitation or regret.

Pirates and Dummies

I used to go up to the Pirate Bay on an almost weekly basis, to see which Paraglyph Press books were listed there. It ceased to be a priority after Paraglyph folded, and I don’t think I’ve been up there for over a year. Then last week I learned that large NY publisher John Wiley & Sons is preparing a multiple “John Doe” style lawsuit focused on torrent piracy of its staggeringly popular “For Dummies” series. So I sailed back up to the Bay to see how bad it is on the ebook side.

For dummies in search of “For Dummies,” my initial impression is that it’s pretty good, which means that for Wiley, it’s pretty bad. The word “Dummies” can be found in TPB’s torrent catalog 691 times, and although some of those may not be “For Dummies” titles, I’m guessing that nearly all of them are. Individual books are listed, of course, but what probably worries publishers more is that a 6.3 GB file containing 572 “For Dummies” books is listed as well. 6.3 GB sounds like a lot. It’s not. It’s about the size of a single 720p feature-length Blu-Ray rip. 572 PDF ebooks in one lump, egad–in truth, I didn’t know that there were that many “For Dummies” books in existence. (GURPS for Dummies is not something I would have gone looking for.)

Alas, the pirates have forgotten about me personally, and for that matter, about Paraglyph Press itself. Only one Coriolis book is listed, Michael Abrash’s Graphics Programming Black Book. (There may be others that weren’t cited with the word “Coriolis;” I didn’t search deeply.) As I said, my own last name isn’t present even once. Much more startlingly, David Brin is listed only three times. Connie Willis, twice. Vernor Vinge, once. Nancy Kress, not at all. Being hot must help; Neil Gaiman is listed 49 times.

One gets the impression that reading isn’t a priority among pirates. To find out just what is, you need a better metric, and The Pirate Bay offers one: the number of complete torrents. “Seeders” are people who make available complete copies of a given file. “Leechers” are those who are currently downloading the file. The more seeders, the more popular a file, and the faster it will download to the leechers. (The protocol is interesting and described well here.)

Although there are hundreds of torrent trackers, the Pirate Bay is by far the most popular, ranking 91 on Alexa. I think it’s pretty characteristic of the pirate world in general. So let’s go count Pirate Bay seeders:

- The top audio book is Double Your Reading Speed in Ten Minutes. 548 seeders. (Irony alert! Near-toxic levels!)

- The top ebook is Do Not Open: An Encyclopedia of The World’s Best-Kept Secrets. 1,442 seeders.

- The top pirated app is Photoshop CS5. 6,412 seeders.

- The top music track is “We Found Love” by Rihanna. 7,010 seeders.

- The top game is The Elder Scrolls. 12,438 seeders.

- The top movie is Conan the Barbarian. 17,422 seeders.

- The top TV show (in fact, the top torrent of any kind) is an episode of “How I Met Your Mother.” 23,259 seeders.

I hope I don’t have to beat you over the head with it: Video is twenty times more popular on torrent sites than ebooks. Down in Dummies land, it’s worse: The 572-book “For Dummies” collection has all of 99 seeders. Neil Gaiman’s best (46) is less than half of that.

So why is a major book publisher suing a relative handful of torrenters? I’m guessing that it’s because it can. BitTorrent is extremely “open” in terms of who’s doing it, and if you’re downloading you’re automatically uploading too. Recording the IPs of people in a torrent swarm is easy. Suing them is dirt simple. Some money can be harvested offering settlements, but at those minuscule usage levels, not much. I’m sure that Wiley wants to exert a “chilling effect” on sharing of Dummies books, and they are–but only in the torrent world. Even though my books vanished from the Pirate Bay, it didn’t take Sherlock Holmes to find them out on the bitlockers and Usenet, which for various reasons are much tougher nuts to crack on the legal side.

Video rules the torrent world because video is big, and the BitTorrent protocol is the most effective way to get video downloaded quickly. Small files like ebooks are elsewhere, unless they’re gathered into massive collections the size of Blu-Ray rips. Ebook piracy seems to be a minor issue today because ebook piracy is mostly invisible. It’s out there, and for all that I’ve pondered the problem, I return to the conclusion that the problem has no solution other than to sell the goods easily and cheaply, and to stop teaching people to be pirates by making the media experience complicated with DRM.

In the meantime, announcing mass lawsuits of torrenters of a specific product line pulls the Streisand chain hard. You might as well yell “Come and get it!” to people who hadn’t known that all 572 Dummies books (or ebooks generally) could be found on torrent sites. This has to be balanced against whatever chilling effect the lawsuits may have, and I can’t help but think that it’s a wash, at best. The real result of such suits over the years has been to push piracy into places where it’s difficult to see and almost impossible to police. The First Principle of whatever we try has to be this: Don’t make the problem worse. If this means that no solution presents itself, we may have to content ourselves with that.

Hephaestus Books and Deceptive Titles

Here’s an emerging story, first pointed out to me by Bruce Baker: There’s a new POD business out there selling free content that isn’t quite what it appears to be. A firm called Hephaestus Books in Richardson, Texas is listing literally hundreds of thousands of POD titles (166,000, as of this morning) on the major online booksellers, including Amazon, B&N, and BooksAMillion. Some are familiar public domain material. Some of them are eye-crossing minutiae that maybe seventeen people in the world would find interesting. Some sound scholarly. (Here’s an example.) But many of the newest sound like compendia of popular modern novels that in no way are in the public domain, like Jerry Pournelle’s CoDominium stories. And for $13.85, yet.

Sounds like. And here’s the catch: The POD books in question do not contain the novels listed in the title.

That would be difficult, considering that most of the books from Hephaestus are 40-80 pages long. They in fact contain discussion about the novels, much of it harvested from Wikipedia, all of it shoveled (presumably by scripts) into a file accessible by POD print machinery. Most of the big-name writers in SF are represented in the Hephaestus catalog, including Larry Niven, David Brin, and Charlie Stross, but lots of far more obscure names are there, too, like Robin Hobb. Check for yourself: Go to Amazon’s search page and type the name of any (reasonably) well-known writer, followed by “Hephaestus.” Prepare to be surprised–after all, there are 166,000 books to choose from. (Alas, don’t look for me. Already checked.)

So what precisely is this? Copyright infringement? Given the scorched-earth penalties called out by the DCMA, I doubt there’s any infringing material in these books. They’d be nuts to do that. Some online have suggested that this might be a legal issue called “tort of misappropriation” of a celebrity’s publicity rights (which, interestingly, are very well protected by Texas law) but I myself don’t think so. There are strong fair-use protections of discussion and criticism of events, things, and people, and a lot of redistributable content online. This seems to be what Hephaestus is selling. If they trip up, it’s likely to be on consumer-protection grounds, since the titles of many of these books are very deceptive. It’s a tough thing to prove, though, and the whole business seems to have been constructed with considerable skill.

One thing I still don’t understand is the cost of the ISBNs. Every book I’ve seen has an ISBN, and the ISBNs appear to be legitimate. ISBNs are not free, and in fact cost about a dollar each, even in blocks of 1,000. Given that the vast majority of these books are never likely to be ordered, even once, the burden falls on the rest to make back the investment in ISBNs given to all of them. ISBN’s for 166,000 books must have cost them about $150,000. That’s a hefty upfront cost for a revenue stream as dicey and unpredictable as this one.

How much they’re making per book is impossible to tell without knowing more about how they’re being distributed. Ingram and similar companies charge fees for mounting POD books on their systems, which would send the upfront cost for the press hurtling into the millions dollars–before they sell a single book. I’m still looking into this, but it’s a head-scratcher first-class. If you know anything more than I’ve summarized here, please pass it along.

Ah, well. This is only the latest emergence of a phenomenon that’s been with us for some time. I call such presses “shovelshops.” The big retailers could kill them in an hour by restricting the speed with which titles can be registered. Even presses like Wiley and Macmillan don’t publish more than a handful of books per day. The Hephaestus business model depends upon thousands upon thousands of books appearing very quickly. If no press can register more than ten or twenty books a day, it’ll take a long time to get the title count to the point where the number of clueless customers begins to pay off.

And then there’s always that sleepy dragon, the FTC, which may or may not be prodded enough to take notice. In the meantime, buy nothing from Hephaestus Press. You’ll be glad you didn’t.