This is Part 2 of an entry I began yesterday.

Nine years ago, I called for the creation of a digital content gumball machine; that is, a Web site that would accept payment and send back a file of some sort, whether a song, a video, or an ebook. It was the start of a popular series and I got a lot of good feedback. I’ve since walked back on several of the original essay’s points, primarily the notion that every author should have his or her own ebook gumball machine, but also the notion that DRM needs to be accomodated. At the time, I thought that while DRM might not help much, it wouldn’t hurt. I think the experiences of Baen and Tor (and probably other imprints) have proven me wrong. Lack of DRM helps. Besides, DRM is what gave Amazon its market-lock, and publishers demanded it. Petard, meet hoist.

The really big lesson Amazon taught us is that Size Matters. What we need isn’t a separate gumball machine for every author or publisher, nor even a clever P-P network of individual gumball machines, though that might work to some extent. We need Godzilla’s Gumball Machine, or Amazon will just step on it and keep marching through the ruins. To compete with Amazon, all publisher/author storefronts must be searchable from a single search prompt. Payment must be handled by the gumball machine system as a whole, via Paypal or something like it. Publishers will probably sell direct, and pay a commission to the firm operating the system.

This could be done. It wouldn’t even be hideously difficult. The technology is not only available but mature. Best of all, well…it’s (almost) been done already. There is a second e-commerce titan in the world. Its name is EBay. (Ok, there’s also Alibaba, which I have never used and know little about aside from the fact that it’s bigger than Amazon and eBay combined. Oh, and the fact that their TMall site is already hosting stores for Chinese print-book publishers.)

I’ll cut the dramatics and get right to the point: The Big Five need to partner with eBay and possibly Alibaba to produce a digital content gumball machine (or two) as efficient and seamless as Amazon’s. EBay’s affiliate store model is a good one, and I’ve bought an awful lot of physical goods on eBay, both new and used, outside the auction model. In fact, in the last few years I’ve bought only collectable kites at auction. Everything else was a fixed-price “buy it now” affiliate sale.

Admittedly, eBay has some work to do to make their purchasing experience as good as Amazon’s. However, they are already providing digital storefronts to physical goods retailers. I haven’t seen any plans for them to offer digital content so far, but man, are they so dense that they haven’t thought of it? Unlikely. If eBay isn’t considering a content gumball machine, it can only be because the Brittles won’t touch it. That’s a shame, though I think there’s an explanation. (Stay tuned.)

A large and thriving eBay media store would provide several benefits to publishers:

- Print books could be sold side-by-side with ebooks. Publishers could sell signed first editions to people who like signed print books (and will pay a premium for them) and ebooks to everybody else.

- Selling direct means you don’t lose 55% to the retail channel. Sure, there would be costs associated with selling on such a system, but they wouldn’t be over half the price of the goods.

- Cash flow is immediate from direct sales. It’s not net 30, nor net 60. It’s net right-the-hell-now.

- Publishers could price the goods however they wanted, at whatever points they prefer.

So what’s not to like?

Readers who have any history at all with the publishing industry know exactly what’s not to like: channel conflict. In our early Coriolis years, we sold books through ads in the back of our magazine. They weren’t always books we had published; in fact, we were selling other publishers’ books a year or two before we began publishing books at all. The Bookstream arm of the company generated a fair bit of cash flow, and it was immediate cash flow, not the net-180 terms we later received from our retailers. Cash flow is a very serious constraint in print book publishing. Cash flow from Bookstream helped us grow more quickly than we otherwise might have.

However, we caught a whole lot of hell from our retailers for selling our own products direct. That’s really what’s at stake here, and it’s an issue that hasn’t come up much in discussion of the Amazon vs. Hachette fistfight: Publishers can’t compete with Amazon without a strong online retail presence, and any such presence will pull sales away from traditional retailers, making those retailers less viable. If the Big Five partner with somebody to create Godzilla’s Gumball Machine to compete with Amazon, we may lose B&M bookstores as collateral damage.

Then again, the last time I was at B&N, they’d pulled out another several book bays and replaced them with toys and knicknacks and other stuff that I simply wasn’t interested in. The slow death of the B&M retail book channel has been happening for years, and will continue to happen whether or not the Big Five create their own Amazon-class gumball machine.

Alas, the Amazon-Hachette thing cooks down to this: Do we want Amazon to have competition in the ebook market? Or do we want B&M bookstores? We may not be able to have both, not on the terms that publishers (especially large publishers) are demanding.

And beneath that question lies another, even darker one: If eBay/Alibaba/whoever can provide an e-commerce site with centrally searchable ebook gumball machine for anybody…do we really need publishers in their current form? Publisher services can be unbundled, and increasingly are. Editing, layout, artwork, indexing, and promotion can all be had for a price. What’s left may be thought of as a sort of online bookie service placing money bets against the future whims of public taste. People are already funding books with kickstarter. B&M bookstores may not be the only things dying a slow death.

So what’s my point?

- Amazon works because it’s a single system through which customers can order damned near any book that ever existed. Any system that competes with Amazon must do the same.

- Digital and physical goods may not be sellable by the same firm, through the same retail channels. How many record stores have you been to lately? We may not like it, but it’s real.

- Neither B&M bookstores nor conventional publishers are essential to keep the book business alive and vibrant. We may not like that either, but it’s true.

- Publishing will probably become a basket of unbundled services. Big basket, big price. Smaller basket (if you can do some of the work yourself) smaller price. (I have an unfinished entry on this very subject.)

- The real problem in bookselling is discovery. This is not a new insight, and however the book publishing industry rearranges itself, discovery will remain the core challenge. You need to learn something about this, and although I’ll have more to say about it here in the future, this is an interesting and pertinent book.

And to conclude, some odd thoughts:

- The future of print-media bookselling may lie in used bookselling. Used bookstores seem to be doing OK, and it’s no great leap to imagine them taking a certain number of new books. Expect it to be a small number, and expect them to be sold without return privileges.

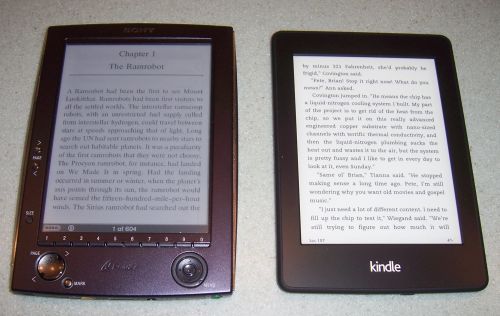

- The book publishing business may fragment into segments that bear little business model resemblance to one another. Genre books work very well as ebooks. Technical books, not so much.

- Change is not only inevitable, it’s underway. Brittle will be fatal.

Any questions?