One of the interesting questions surrounding the failures of memory that I’ve been describing is whether there’s some “motivation” for the distorted memory. Any time I see any person I know and value who’s smoking, I cringe. Dottie and Sarah were good friends who shared some context with me, so some of the concern I felt when I saw Dottie smoking may have “bled over” into memories of Sarah in a similar context.

In my readings I’ve seen examples of people who remember incidents in ways that put them in a slightly better light. For example, nobody likes to remember themselves doing stupid things, so a memory of a faux pas may be “tweaked” to be a little less faux. Memories on which your self-esteem doesn’t hang might come down through the years a little more accurately. If there is some sort of inner redactor that attempts to make our remembered lives more tolerable, one might hypothesize that memories without importance might be less vulnerable to distortion than memories of things with emotional baggage. Psychologists used to believe this, but experiments like the Challenger study blew holes in the older notion that “flashbulb memories” are more accurate than mundane memories of no great significance. So how well do insignificant memories survive?

It’s hard to tell, of course, until you come across objective documentation of some little thing that doesn’t align with what you remember of it–and insignificant things are probably the things most easily forgotten. I do have an example, though, and it’s an odd one.

Back in 1999, the editor of Kite Lines magazine asked me to write a mini-memoir of my experience as a kid flying Hi-Flier kites. I began by sitting down in a chair with a notepad and taking notes on everything I could recall about the dime-store paper kites I had flown from 1961 to 1968 or so. I went down the list, describing the commonest Hi-Flier kites and my impressions of them, including as many details as I could clearly recall.

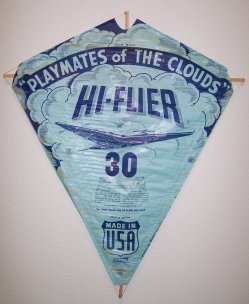

The article was a great success, and after their exclusive period expired, I adapted the article to a Web article on my own site, which I have expanded over the years as new information has come to hand. In the article I described probably the most common of all Hi-Flier’s small paper diamond kites, the “Playmates of the Clouds.” (See example at left.) The three varieties of Playmates differ only in what’s immediately under the flying wing: A number, the words “Little Boy,” or nothing at all. I remembered kites with the number 30 as probably being the most common–but I remember flying Playmates with other numbers, particularly the number 94. I also clearly recall having a Playmate tagged with the number 6, and vaguely remember a number in the 40s somewhere.

The article was a great success, and after their exclusive period expired, I adapted the article to a Web article on my own site, which I have expanded over the years as new information has come to hand. In the article I described probably the most common of all Hi-Flier’s small paper diamond kites, the “Playmates of the Clouds.” (See example at left.) The three varieties of Playmates differ only in what’s immediately under the flying wing: A number, the words “Little Boy,” or nothing at all. I remembered kites with the number 30 as probably being the most common–but I remember flying Playmates with other numbers, particularly the number 94. I also clearly recall having a Playmate tagged with the number 6, and vaguely remember a number in the 40s somewhere.

After writing the Kite Lines article, I started watching for paper kites on eBay, and when the feature appeared, put a saved search on “Hi-Flier” and “paper kite.” Lots of kites have marched past the All-Seeing Eye of Ebay since 1999. I’m sure I’ve seen close to 1,000, and perhaps more. Playmates of the Clouds kites are very common, and I’ve bought a couple for use as wall art. But never in those ten years and on probably 200 Playmates kites have I seen a number other than 30.

Back in 2007 I heard from a chap who called me on it: He’s an avid collector of classic kites who has hundreds of his own and seen many more. He told me that the number 30 on Playmates of the Clouds kites indicated the size of the kite (it’s 30″ down the vertical stick) and that Hi-Flier never printed a Playmates kite with any number other than 30. I must have misrecalled.

I guess. But my memory of that magenta-on-white Playmates with a 94 on it is clear, and has some context: I had it for an unusually long time, for a paper kite. I flew it down in Blue Island at Aunt Josephine’s house on two rolls of string, out over the big railroad yard near their house, and got it back intact. I flew it for the rest of the summer, and only dumped it when I left it lying out in the rain overnight and it got soaked. It was a good kite (and a lucky one, mostly) and if it didn’t have a 94 on it, why do I remember the 94? Why not 48, or 57? Why don’t I just remember the 30?

It was never a big deal. The numbers on Playmates kites were significant to me only in that I thought they were stupid: The digits were just 2″ high, and after the kite was more than 50′ out, you couldn’t read them anymore. I assumed (with 12-year-old geek logic) that they were there to allow you to tell your kite from all the other Playmates kites in the air. Wouldn’t work. Rolls eyes. End of story.

So: The kites that I remember so clearly didn’t exist in the form that I remember them. This seems weird to me because there’s no motivation for the redaction: Remembering them differently doesn’t affect anything, and it’s a little weird that I remember small things like numbers on kites at all.

The point seems to be that we don’t always remember details well, whether the details are emotionally significant (“Where were you when Challenger exploded?”) or practically background noise (“What number was on your favorite kite?”) I’m guessing that in every life there are a staggering number of little disconnects between what we remember and what really happened, and we’re unaware of it only because we don’t generally have confirming documentation of all the little things that we remember–and mostly, we don’t care. When we notice such a disconnect, we snort, say, “heh!” and move on. No big deal.

I’ve gone on for a few days here because somebody asked me recently if I was ever going to write my autobiography, and I spent a little time thinking about it. Suppose I did: Would what I wrote bear a useful resemblance to what in fact happened? And if not, what’s the point of autobiography? How much, in fact, can we trust any kind of memoir? If memoir is read mostly as entertainment, why not just write fiction?

Perhaps we do. As best I can tell, our brains write our memories as a kind of historical fiction, drawing the broad strokes from reality and then filling in the gaps with whatever makes the best yarn. I find this troubling in a weird way, but I guess I’ll just have to get used to it: The bulk of what’s happened in my life has not only been forgotten, but was never actually remembered to begin with. If any revelation can literally be called humbling, well, that’s the one.

While passing through western Nebraska, we stopped at a

While passing through western Nebraska, we stopped at a