Well, that won’t be the title of a Top 10 song, fersure. However, it’s true: I went to my first SF convention in five years. It’s called LibertyCon. It was in Chattanooga, Tennesee, thereby taking my list of un-visited states down to 11. I had a truly marvelous time. I’m going next year, 1,500-mile air distance be damned.

I’ve never seen anything quite like it.

Actually, that’s not entirely true. Libertycon reminded me of the 1970s, minus the hormones, the frizzy hairdos, and the leisure suits. Back in the 70s, when we went to cons it was for the writing, the art, the authors, the huckster room, the parties, and all the other people who were there. We didn’t go to cons to talk about politics. In fact, we avoided the handful of losers who insisted on talking about politics, and if they got too much in our faces, we chewed them out. This element of con culture began to disintegrate in the mid-1980s, which, not coincidentally, is about the time I stopped going to cons, beyond the occasional Worldcon that was within easy driving distance.

Just imagine! There were no panels on how Gambians are under-represented in fantastic fiction, nor panels explaining why setting stories in Gambia is cultural appropriation. The insufferable John Scalzi was not present, and was not yelling that everyone could kiss his ass. (He does this so much I wonder if he’s mispelling “kick.”) There was no code of conduct granting the concom the power to throw you out of the con if you said something that somebody at the con didn’t like.

No. We listened to panels and solo presentations about designing alien species, collaborating on writing projects, overcoming writer’s block, satellites vs. space junk, future plagues, junk science, the New Madrid fault system, the future of military flight, space law and space treaties, writing paranormal romance (with the marvelous subtitle “Lovers and Stranger Others”), inventions and the patent system, the future of cyberwarfare, cryptozoology, and much else. See what’s not on that list? Well, I won’t drop any hints if you don’t.

Note well that this is about con programming and con management. Here and there politics crept into private conversations of which I partook, but I heard neither Trump bashing nor this “God-Emperor” crap. There was occasional talk of governance, which some of us called “politics” in ancient times before partisan tribalism polluted the field. There was much talk of guns, and nobody had to look over their shoulders before speaking. There was also much talk of swords and knives and how such things are made.There was a great deal of talk about whiskey, but then again, this was Tennessee. (And nobody held the fact that I don’t like whiskey against me.) There was, in fact, talk about damned near everything under and well beyond the Sun. What was missing was shaming, whining, and tribal loyalty signaling. (There is no virtue in “virtue signaling.”) It was nothing short of delicious.

The list of authors present was impressive: my friends Dan and Sarah Hoyt, John Ringo, David Weber, Tom Kratman, Peter Grant, David Drake, Jason Cordova, Stephanie Osborn, Karl Gallagher, Lou Antonelli, John Van Stry, David Burkhead, Michael Z. Williamson, Richard Alan Chandler, Jon del Arroz, Declan Finn, Dawn Witzke, and many others. Baen’s Publisher Toni Weisskopf was the con MC, but she always attracted such crowds that I never managed to get within several feet of her. Space law expert Laura Montgomery was there, and I lucked into breakfast with her and her friend Cheri Partain. I also had some quality time with master costumer Jonna Hayden.

In truth, I had quality time with quite a number of online friends, most of whom I met at the con for the first time. I made a special effort to talk to indie writers. Most said they were selling books (generally ebooks on Amazon’s Kindle store) and making tolerable money if not a steady living. The question that has been hanging over the indie crowd for years is still there, flashing like a neon sign: How to rise above the noise level and get the attention of the staggeringly large audience for $3-$5 genre fiction ebooks. I talked to a number of people about that, and there are still no good answers.

But the conversation continued, untroubled by identity politics, or indeed politics of any stripe. The food was good. But then, I don’t go to cons for the food. I didn’t get a room at the Chattanooga Choo-Choo, which is in fact a weird accretion of a train station, some old train cars, and a conventional hotel building. I stayed at the Chattanoogan a few blocks away, just to be sure I had a dark, quiet room to escape to when the revels were ended each night. About all I can complain about are aching feet, but then again, that’s why God created Advil.

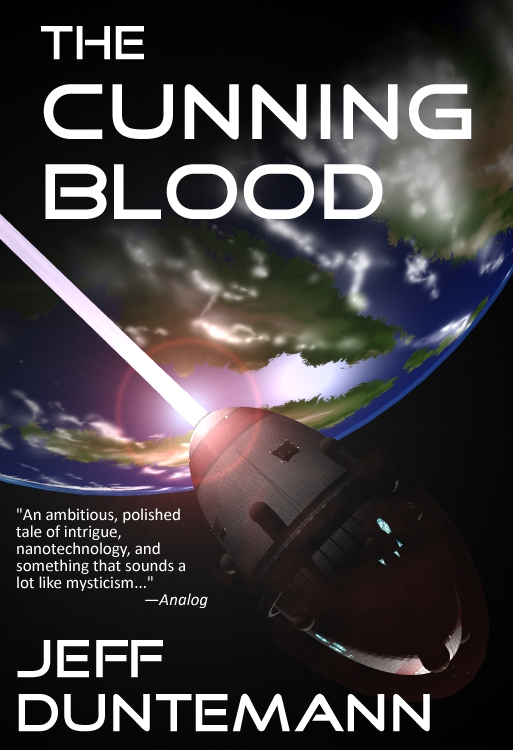

As best I know, there is nothing like LibertyCon anywhere in the country, and certainly nothing in the West. I will be there next year, with sellable hardcopies of The Cunning Blood, Ten Gentle Opportunities, the Drumlins Double, Firejammer, and (with some luck) Dreamhealer. Many thanks to all who spent time with me, especially Ron Zukowski, Jonna Hayden, and the Hoyts, all of whom went to great lengths to make me feel welcome and part of the club.

It’s amazing how much fun you can have when you agree with all present to leave the filth that is politics outside the door, and ideally across the county line. That’s why LibertyCon is what it is, and why they limit membership to 750. My guess is that there is room for other events like LibertyCon elsewhere in our country. If you ever run across one, please let me know!