5

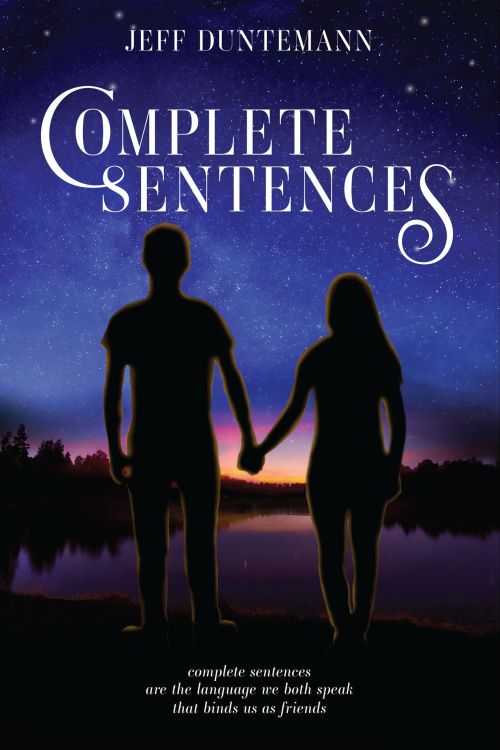

Three flashlight beams lit the campground road. With Charlene to his right and Marianne to his left, Eric led the way to where the road swung toward the lake and the sand came right up to the crumbling edges of the asphalt. A slow breeze like a soft warm breath came off the lake, heavy with the scent of summer, and gentle water sounds joined with the August cricket song. Charlene’s left hand gripped Eric’s right arm just below the end of his T-shirt sleeve. Her touch was still magical, perhaps moreso because she was putting her weight on his arm whenever she took a step. She could walk because he was there to help. He tried to drive the thought out of his head, but with each tightening of Charlene’s hand on his bare arm, the intoxicating thought returned: She needs me!

The trio walked out onto the beach until they had gone midway across the sand, within several yards of the water. Eric scanned the horizon. “This should be good, right here.”

Charlene squeezed his arm one last time, and pulled herself against him. She tipped her head until her temple touched his shoulder. “Thank you,” she whispered.

“Whatever I can do to help,” he whispered in reply. He looked up again as she drew away. “Turn off your flashlights.” The three lights flicked out, leaving them in darkness.

No one moved nor spoke as their flashlight-dazzled eyes gradually adapted. Above them, in an order Eric had witnessed under many dark Wisconsin skies since he’d been a small boy, the stars were coming out. First, the brightest of the brilliant: Antares, Spica, Vega, Deneb, Altair, all torches of the night. And one more, in their league but not of their kind: Saturn, a steadfast untwinkling pale yellow in the southeast. As his eyes grew more accustomed to the dark, the second-string stars appeared. Eric could name some but not all, and they were everywhere, the framing members of the constellations, not torches but-he grinned-two by fours. Soon after emerged the multitudes of lesser magnitudes, down to the limits of his eyes to discern. Finally, meandering down the sky toward Sagittarius in the south, a river of pale stardust, the Milky Way.

“Wow!” Marianne said to his left. “I’m lost already!”

Charlene tsked. “Nobody’s lost with Eric around.”

“Especially you,” Marianne muttered.

It was a girl thing; Eric guessed that he wouldn’t understand. He shrugged, and knelt beside Marianne. “We’ll start right here. Turn toward the north.” He gripped Marianne’s hand and pulled her around until she was facing the same way he was. He noted that there was no magic in Marianne’s hand, as there was in Charlene’s. “Right over the trees in the north. Look hard. You’ll see the Big Dipper.”

He felt her hand tense. “Yes! It’s there! I see it! It’s really big!”

“Yup. That’s why it’s not called The Medium-Sized Dipper. Now look at the bowl of the Dipper. Find the two stars at its left side.”

“I see them.”

“Now draw a straight line between those two stars, and extend it upward until the line hits another star.”

Marianne remained silent for a few seconds. If she had never looked up at a sky as crisp and clear as this, she might have trouble separating the Dipper’s canonical stars from the clutter of fainter lights everywhere around them. So he was patient. She was only nine.

Charlene placed her hand on his shoulder and squeezed twice. Eric suspected she was thanking him for catering to her bratty little sister. Again, he felt Marianne’s hand tense as her eyes learned the skill of separating the brighter lights from the fainter.

“Yes! It’s there! What star is that?”

“Polaris. The pole star. The whole sky revolves around it.”

“Wow! And that’s really because we’re rotating, right?”

“Right. And Polaris is the end of the handle of the Little Dipper. It’s harder to see because its stars are fainter. It’s about the same shape as the Big Dipper, but smaller and aimed the opposite way.” Eric lifted lifted Marianne’s hand until it pointed to one side of Polaris. “See it?”

Eric could almost feel the epiphany that came upon Marianne. “I do! Wow! The Little Dipper! How do you knowall this stuff?”

Eric released her hand and stood. “I read books. Lots of them.”

In one rapid-fire lesson, Eric took Charlene and Marianne through the hallmarks of the late summer sky: Scorpius, the teapot of Sagittarius, the Summer Triangle, Delphinus, the Great Square of Pegasus, and all the bright stars from horizon to horizon. Halfway through the tour, he felt Charlene’s soft, small fingers wriggle their way between his. He lost his train of thought, and caught himself wondering where Achernar was. No, wait-that wouldn’t be visible this early until October. Only one thing was clear in his mind:

A beautiful girl was holding his hand.

“Please show me Lyra,” Charlene asked. Eric’s heart was pounding. “In the book I read, it actually looked like a harp.”

Lyra was almost at the zenith. Eric craned his neck back until he felt it pop. “Straight up. A very bright white star with a touch of blue. That’s Vega, Alpha Lyrae. You can’t miss it.”

“Yes! It was so bright and beautiful in that book. I wanted a T-shirt with ‘Lyra’ on it, printed in gold ink on black above the constellation. I wanted it to be my symbol.”

Eric pointed at Vega. “Lyra is a parallelogram, with Vega above and to the right of it. Four stars. It would be easier to see if it wasn’t straight up.”

“That’s easy to fix,” Charlene said, and sat on the sand. She stretched her legs out toward the water, and lay down. “I see it! Perfectly! It’s better even than the book!”

“No picture of the stars ever does them justice.” Eric pointed again, almost to the zenith. “To the right of Lyra is Hercules. It looks like a keystone.”

Charlene grabbed Eric’s ankle. “Don’t look straight up like that. You’ll hurt your neck. Lie down like me.” She turned to her sister. “Marianne, you too.”

“I dunno about this,” Marianne grumbled, but complied.

Eric hesitated, looking back toward the trees that separated the beach from the tent sites. He had done plenty of observing flat on his back. It was certainly a more comfortable position for looking at the zenith. But he’d never done it with a girl-or anyone else-beside him.

Once Marianne was stretched out on the sand, he sat down between the two girls, took one more nervous glance toward the road and the trees, and lay down himself.

The lecture began again. He explained how you could follow the curve of the Big Dipper’s handle and “arc to Arcturus” and later, following the same general curve, continue to Spica. He showed them the close pair of stars called the “cat’s eyes” at the stinger end of Scorpius. Wistfully, he told them that if he had his telescope finished, he could show them the rings of Saturn.

Eric heard Charlene wriggling toward him on the crunchy sand. Her hand gripped his right arm. The next thing he knew, her head was on his shoulder, her body pressed against his side. He had the intuition that she was paying but a fraction of the rapt attention that she had shown only minutes before. His tour of the sky stopped abruptly.

A slow, silent minute ticked past. Eric oscillated between elation and dread.

Dread won, in the form of Marianne’s agitated voice. “Hey, Shar, what are you doing over there? If mom sees us lying down like this, she’ll be mad.”

“Your mom is always mad.”

“You’re lying down and hugging a boy!”

Charlene looked over Eric’s recumbent body at her sister “I’m hugging my friend.”

“He’s a boy. It’s not like hugging mom.”

Charlene’s voice grew sharp. “Your mom hugs you. She’s never hugged me. Ever. And your dad never hugs anybody. Who am I supposed to hug?”

The last thing Eric needed was for the girls to get in a screaming match across his ribcage. The pale green luminous hands of his watch showed 9:41. He had promised Mr. and Mrs. Sawyer to get their daughters back to the site before ten. This was as good an excuse as any.

“Um, we have to go home now. It’s quarter to ten.”

Eric helped Charlene to her feet, with Marianne standing nearby, her arms crossed. Charlene rubbed her eyes and cheeks against the sleeves of her T-shirt. Once their three flashlights were lit, they walked back to the tents without another word. Charlene’s limp was still obvious, but she did not take Eric’s arm. And one faint smile was her only reaction when he finally said ‘G’night”.