- Please read this short article by Mark Shuttleworth. I’ve been saying this for years, but he’s a lot more famous than I am: Tribalism makes you stupid. It also means that you are owned, and are not a free man or woman.

- The Insight debugger front end for gdb has been removed from all Debian-based Linux distributions, and is not present in Ubuntu 10.4. The Debian package for Insight has been criticized as “insane” and unmaintained, and I’m curious: Has anyone here used it in recent releases of Fedora or OpenSuse?

- Autodesk founder John Walker has an interesting free Web toy for Greasemonkey, which attempts to spot “media trigger words” and alert you when weaselspeak is being attempted. (Thanks to Jason Kaczor for the tipoff.)

- Oh, no! It’s the Pluto Effect for dinosaurs! Triceratops is actually an immature Torosaurus!

- Man, turn your head for ten minutes and there’s a whole new kind of punk out there. But this one I may actually like: Dieselpunk. Think Art Deco urban fantasy, with the cultural clock set at 1920-1945. This might include the first Indiana Jones movie, and certainly one of my personal favorites, The Rocketeer. Lessee, we still need Musketpunk, for gritty urban fantasy in 1780 Philadelphia. Ben Franklin with tattoos. Could work, no?

- Don’t be drinkin’ Diet Mountain Dew while reading this site. Trust me.

- There is an entire news site devoted to good news. Perky people like me and Flo read it every day now.

- Sheesh. What’s wrong with “Hi! Is this seat taken?” (Wait, no, that was the 70s. And purely analog.)

- I don’t think I posted a link to this back in April, but I should have. There’s a rectangle of this identical cloth hanging on my workshop wall as framed art. Pray without ceasing, even when you’re soldering up a regenerative receiver.

software

Odd Lots

App Inventor for Android

Whoa. Yesterday morning Google took the wraps off App Inventor, a visual development environment for the Android mobile OS. I’m still trying to slurp from the firehose, even though I’m finding that all the hoses have basically the same information, and in truth not a great deal of that. But I’ll tell you right now: It stopped me in my tracks on the iPad decision. As of yesterday morning, I wanted something that runs Android. The new search is on.

You know me. I’m the Visual Developer guy, and the fact that my magazine’s been dead for ten years doesn’t change that. I still believe that visual metaphors for programming are not only useful but necessary, if certain kinds of software development are to happen at all. (More on this below.)

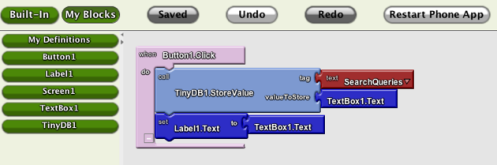

If you haven’t looked into App Inventor at all yet, a very good place to start would be Jason Kincaid on TechCrunch. He’s got a good overview and some screenshots (including the one I show above) that will give you a sense for what Google’s cooking up. I’ll summarize here. App Inventor has two major subsystems:

- The Designer is basically a form designer, not conceptually different from that in Delphi, VB, and many other more recent environments. You drag UI components from a palette and arrange them on a form.

- Far cooler (if less proven in its approach) is the Blocks Editor. Here’s where program logic happens, and it happens by snapping together logic blocks that look literally like jigsaw puzzle pieces. Clusters of blocks become event handlers. You connect a cluster to an event generated by a component on the form, and the blocks in that cluster execute.

(This may not be the correct jargon. Please understand that I don’t have an instance to play with yet, so all I can do is relay what I’ve read from the fortunate few who were given early copies.)

I knew what the major problem was going to be before Jason told me: In any system like this, you’re limited by the selectable elements on your palette. He didn’t mention where the blocks come from (I assume they’re written in Java using some relative of the MIT Open Blocks technology) nor whether user-created blocks will be importable into the product as shipped. I’m a lot less worried than he seems to be about this, because Google isn’t stupid, and they know damned well that the system lives or dies by the richness of the set of available logic blocks from which the apps are generated. If it’s anything like an open system, there will be an explosion in third-party blocks once a few Java guys get the system and figure out how to do it.

Jason provides some screenshots with his article, and I borrowed one above to get your attention. Here’s another page with a description of a more complex app, with a much more representative Blocks Editor display.

There’s not a lot more that I can say about App Inventor itself, at least until I can get a workable instance installed here. But it’s been interesting seeing all the dorks in the comments to the news stories, dumping on the system for its simplicity, and for the (frightening) possibility that the hoi-polloi will be able to use it to write their own software. They scream the obvious: You can’t write a word processor with a tool like this!

Fersure. And that’s not what it’s for. I’ll respond with something that should be equally obvious: The mobile phone environment is fundamentally different from the desktop environment. From the beginning, it’s been about smallish apps that do one or two things of interest, and no more. Mobile phone computing for the most part is about getting in, doing something with a few quick clicks, perhaps reading the screen, and getting out. The apps are very focused and often extremely specialized. Some are obviously going to be a lot more difficult to write than others, but a useful mobile app does not necessarily require man-years of development time.

And if it ever did, it won’t anymore once App Inventor hits its stride.

I think that I’ll use App Inventor for the same reasons that I use Delphi: To play with ideas, see how things work, and gen up one-time test apps that may lead in useful directions. I’m guessing that App Inventor will enable people to create apps for an audience of one–themselves–and not have to spend six months of free time to do it. Companies may experiment with different approaches to mobile computing without having to commit millions of dollars in dev costs to any one approach, just to see if it’s useful or even doable.

I have never had a smart phone, and I’ve been waiting for my current cell provider contract to expire early next year before getting one. I may have to accelerate the schedule a little. This thing’s making me itch in places I haven’t itched in for a long time.

Odd Lots

- Before GPS, there was…rolled paper. I’m not sure how useful a one-dimensional scrollable map is, but it was a good start. (And now, all you steampunkers, figure out how to do the same thing in two dimensions.)

- Shortwave radio and one-time pads are still being used, as we discovered in the recent Russian spy foofaraw. Slate’s done a decent overview of number-station covert communication. The late Harry Helms wrote a lot about these, and most of what I know came from his books. Some technologies just don’t get better over time. They were optimal from just about the beginning.

- This Lifehacker tutorial tells you in agonizing detail how to install OS X Snow Leopard in a VirtualBox VM. Cool enough–but when did that become legal? (My guess: It didn’t.)

- From Pete Albrecht comes a pointer to an item describing a proposed copyright law in Brazil that provides penalties for attempting to limit use of public-domain material, or fair use of copyrighted material via DRM. That is a remarkably good idea. (Maybe we’ll see the Viagens someday after all.)

- This looks real (i.e., not Photoshopped) but as at least one commenter has pointed out, there seems to be no way to get inside. Maybe it’s the ultimate RC car.

- Speaking of cars, in reading the comments for this Wired Blog article (titled “What’s the Fastest You’ve Driven?”) I felt old and frumpy. The fastest I’ve ever driven in my life was 95 or 96 MPH: in 1971, in my mom’s battered teal-green 1965 six-banger Chevy Biscayne, northbound on the Edens Expressway just before the I-290 junction…in the rain. Why? I no longer remember. And that’s probably just as well.

- And yet more about cars: Buss Ford Lincoln Mercury in McHenry, Illinois posts YouTube video endorsements from their happy customers. Buy a Merc before they’re gone…and be famous! (It worked for Carol’s sister and her husband.)

- And now, for quite enough about cars: Pete Albrecht reminds us that in 1973 somebody glued the rear portion of a Cessna Skymaster to a Ford Pinto, and it flew…for awhile. (What do people say? “Don’t fly 70s cars?” Uh, yeah.)

- DARPA wants a flying submarine. They should ask Irwin Allen. Or Tom Swift, Jr. (Thanks to Frank Glover for the link.)

Realtime Cloud Logging to Spot Band Openings

(Note: This is a total ham radio geek-out entry, so if such things make your eyes glaze over, be advised that there’s an extreme glaze warning in effect until at least tomorrow morning.)

Anyway. I stumbled on a band opening yesterday by accident: I scanned the 6 meter band, expecting its usual near-silence, and instead heard something like a continuous pileup from 50.2 up to 50.6. Such openings happen semiregularly, especially in the summer and during sunspot maxima, but they’re not reliably present when you want them. Typically, people either monitor the bands for openings using a panadaptor (a way to visualize the whole band at once, often built into high-end radios) or they hear about it from their friends via Skype or some other chat system. (Hey Jeff! 6 is going batshit nuts!)

While copying my notesheet to my log last night, I thought of a better way. Suppose there were a sophisticated Web app allowing people to record their contacts in a central database off in the cloud somewhere. Serious contesters work their radios with both hands on a keyboard these days anyway, but they’re logging their contacts locally, on their own PCs. If enough people were logging enough contacts online in realtime, you could plot those contacts on a map as great-circle lines between one station and another. If you wanted, you could age the plots, so that a given line was displayed on the map for a selectable period of time, say the past fifteen minutes. Older plots would vanish and new ones would be continually added. What you’d have is a lookback time window onto what’s happening on the ham bands, plotted geographically. If you click on the “6 Meters” map and alluva sudden there’s a thick web of lines between Colorado and the east coast, you’d know that there’s a band opening underway.

This would be possible in part because the geographical coordinate locations of stations are implicit in logged contacts. Base (at home) stations are licensed by the FCC to particular addresses, and these addresses are matters of public record, easily queried by software. Mobile stations aren’t required to be at any particular location, but GPS logging for mobiles is possible, and I think has been done, if not commercially. Plus, there’s another way: More and more people (especially on higher bands like 6 meters) log the “grid squares” of the stations that they’ve worked. There’s a system for tagging 2 degree by 1 degree rectangles of the Earth’s surface, such that each rectangle has a 4-character callout. (There are an additional two characters of precision that almost no one uses.) My own is DM78. Here’s a map for the US and for the Earth as a whole. Plotting a line between DM78 and EM94 isn’t hugely precise, but it will tell you that radio signals are propagating usefully between central Colorado and northern South Carolina, and that’s all most of us need to know to make us scramble downstairs and turn the radio on.

I think this is one case where doing something out in the cloud that was previously done locally provides benefits that local storage alone does not. The whole point is to brag about how many locations you’ve worked worldwide, so privacy is not an issue. (If it is, just keep your logs local.) And the benefit of online collaboration is knowing just what propagation paths are open at any given moment of the day. I’d pay a quarter for that, or at least provide data by logging contacts.

I looked around just now to see how close we are, and whereas there are a couple of online logging systems in operation, they are nothing even close to realtime, and none that I can see makes any attempt to plot propagation paths for logged QSOs. That said, nothing I call out here is rocket science.

So. Did I miss something somewhere? And if not, what Ajax wizard is going to give this a try?

Odd Lots

- The $35 Atlantis word processor (see my entry for June 18, 2010) installs effortlessly under Wine and runs without a glitch under Linux. (It has a Platinum compatibility rating, and they don’t get any better than that.) If you’re doing or considering ebook development under Linux, it generates a very good EPub file, and is quite fast and extremely low-profile. (1.5 MB!)

- Doesn’t Popular Science tell us this (and just as emphatically) every three or four years? I’ll believe it when I actually see zepps flying over my house.

- From Bob Fegert comes word that Ray Kurzweil hopes to shake up the ebook business with his still-unreleased Blio reader. I’ve known of Blio for some time; what’s new is the partnership with Toshiba to create a Blio ebook store supporting PDF, XPS, and EPub books. However, what may make Ray the new kingmaker in the ebook world is a recent Federal requirement that universities make their e-readers accessible to the blind. Blio will do that very well (as you might expect, given Kurzweil’s history) and the reader is capable of rendering textbooks to an extent that most other ebook software/hardware combos simply can’t. Much to watch here.

- Having just spent a great deal of money changing out my glasses to a new prescription, I think this Android eye-test app is clearly and crisply brilliant.

- From the Words-I-Didn’t-Know-Until-Yesterday Department: Cyberlocker, a cloud-based file-hosting site. The term is generally used of sites like Rapidshare, which are coming to be seen by Big Content as the greatest single offenders in the file-sharing wars.

- Just as Shrek is selling Vidalia onions, I heard from a reader that Wallace & Gromit not only put the Wensleydale cheeses on the map, but with the power of cartoon branding brought the cheeses’ producer back from the brink of bankruptcy.

- Rich Dailey N8UX writes to tell us that the original Idle-Tyme rolling ball clock is back in production again, after 25 years. I saw one in a store window I don’t know how many years ago and giggled a little at the product’s inherent audacity, but it had a following, and I bought a plastic knockoff in the late 70s. The clock broke, but I still have the balls in a drawer somewhere. Read the history page; the inventor (like a lot of inventors) was a very interesting man.

Review: The Calibre Ebook Management System

I tried Calibre when it first came out a little over two years ago (v0.4.83) and was reasonably impressed. It did everything it said it did, reliably and without much fuss. Alas, I didn’t test most of its features back then, especially its file conversion modules. I’ve done a lot more in the past week, and overall I’m pleased.

The current version is 0.7.6, and author Kovid Goyal posts updated releases frequently, as often every couple of weeks. That’s amazing for a GPLed app, but Calibre itself is amazing in its way. If you install no other ebook reader or manager, get Calibre. It’s a Python app, and can be downloaded for Windows, Linux, or Mac.

There are three general aspects to Calibre:

- It’s a sort of jukebox for ebooks: a simple database manager that allows you to browse your ebook collection, search for individual titles, and edit metadata by individual title or in bulk. It can send books to any of a growing list of hardware readers.

- It’s a collection of import/export modules behind a GUI, allowing you to take an unencumbered ebook in one of a long list of formats, and export it to a different format out of that same long list.

- It’s an ebook viewer that can render ebooks for reading in most popular formats. When a format isn’t supported, Calibre attempts to launch the associated app to render the book.

All three aspects work well, though I ran into some problems with format conversion. I tested Calibre by importing basically every ebook I have on disk, which at this point isn’t all that many. I still don’t have a portable reader device that I like, and I don’t read a lot on my PC display. So I went and got a bunch of things from Project Gutenberg (including all the pre-1923 Tom Swift Senior books) plus some religion journals and other PD oddments from Google Books, and ended up with about 150 titles.

Calibre copies imported ebooks from their original locations to a separate directory, and it operates only on those copies, leaving the originals alone. (This means that the space your library takes on disk will basically double, though I doubt that this is an issue in an era of 2 TB hard drives.) It controls the filename of each file, and imposes a filename by running a regular expression against the title and author name in its database. Change a book’s title in the database, and the filename changes in sync. Delete a book, and only the imported copy in the Calibre directory goes away. Your originals are not touched.

Once you import the ebooks you own, plan on spending some time editing the metadata. Calibre uses a regular expression to extract an author and title string from each file, and although you can change the regular expression if you want, there’s no broadly accepted standard for ebook filenames, and you’ll find that many of your books have the author name in the title field or vise versa irrespective of the expression Calibre uses. You can specify a series name and number for books in series; e.g., Tom Swift, Sr., Volume 12. There are additional fields for publisher, ISBN, pub date, and comments, and if a cover image is present in a book, a thumbnail will be displayed. There is a tagging system with a tag manager.

Sorting out the metadata was a fair bit of manual labor, even for only 150 books. You can do updates on several books at once; for example, I highlighted all the Tom Swift books and set the Author field to Victor Appleton in one operation. If you have many hundreds or perhaps thousands of ebooks (and I know people who do) good luck; you’ll need it. There is autocomplete on fields and that helps, but there’s an irreduceable amount of keystroking that has to happen to get the most from the database browser.

The ebook viewer is as good as I’ve tested so far. It renders almost every ebook format I’ve ever heard of, including the comic book formats and PDF. (You can configure it to launch an external app to handle a specific format if you choose; for example, I open CBZ and CBR files with Comical.) For EPub and MOBI files, at least, the reader automatically maintains a bookmark to the last opened location in the book, and when you reopen a book, the cursor goes right to that bookmark. (This is not true for LIT, PDB, , and LRF books.)

About the conversion modules I have mixed feelings, and the problems are probably not all with Calibre. I converted my EPub version of the Beyschlag Old Catholic history to LRF, MOBI, and PDB. Results were so-so. One problem with the LRF export was that the font size was inconsistent: Parts of the text were rendered in larger type than others, and I can’t tell (yet) if that’s an issue with Calibre’s LRF viewer module or with the conversion process from EPub to LRF. The conversion to PDB stripped out all the formatting, including italics, and that does appear to be a problem with Calibre. MOBI kept the italics but didn’t center the author lines. Calibre seems happiest dealing with EPubs, and conversion from other formats to EPub works better.

Note that Calibre doesn’t deal with DRM-encumbered files at all. That’s fine with me, as I won’t buy DRM, but you need to keep it in mind if you’re looking to read DRMed books on your PC; Calibre is not the item for that.

I also installed Calibre under Linux, and I moved my entire Calibre database over to the Linux machine by simply copying the Calibre books directory to a thumb drive, and then copying the directory from the thumb drive to a folder in my home directory and telling Calibre to use it. As best I could tell, there were no functional or performance differences between the Windows and Linux versions.

There isn’t a lot of downside to Calibre. Opening and rendering an ebook on the internal reader can be slow if it’s one of the more sophisticated formats. (Txt and .rtf files open very quickly.) The viewer doesn’t downsample cover images very well when displayed at less than their native resolution, though that’s a quibble. (Reduce the display size on my Old Catholic history epub and you’ll see what I mean.) Adding bookmarks seems to take more time than it should, especially on longer books. The program crashed once when I had a lot of windows open. (These included Thunderbird 3, which seems to be causing a lot of weirdness recently.)

Calibre doesn’t help you create ebooks; that’s not what it’s for. And some issues with the conversion modules are going to keep me looking for reliable ways to make MOBIs, LRFs, and PDBs out of my EPubs. However, in terms of an ebook manager, it’s just short of stellar. The viewer modules work reasonably well, particularly with files created “natively”–that is, not converted from one format to another.

Basically, the ebook business is still mighty young, and I’m not surprised at how random things still are. Among ebook-related software products, Calibre is the least random of anything I’ve yet tested, and at this crazy stage of the game, that’s high praise.

Highly recommended.

Odd Lots

- Several people have asked me what I think of the Calibre ebook reading, management, sync, and conversion system, and that’s in fact what I’ve been fooling with in recent days. There’s a lot in the package, way more than in any other single ebook reader or manager that I’ve yet seen. A review will follow as time allows.

- I follow this site every day, and I may be a little jaded, but this image (from June 25) made me gasp. (Don’t forget to mouse over it for a guide to what you’re seeing.)

- And if you have any interest in the closest star to Earth, this site should be on your short list.

- From the Words-I-Didn’t-Know-Until-Yesterday Department: Revendication, an old word for “restoration.” Found in Letters from Rome on the Council by “Quirinus” (Acton, Dollinger, and Friedrich), 1870.

- From Jim Strickland comes a pointer to a skin-mag pinup…hold the skin. (C’est si bones…)

- Here’s an interesting list of apps built with FreePascal and Lazarus, an open-source Delphi workalike. I’m going to try some of this stuff, because if it breaks, I may have a fighting chance of fixing it.

- Here’s the best description I’ve yet seen of why broadband in this country is as weak as it is.

- A tie-in with the Shrek movie series has apparently made Vidalia onions this summer’s hot item…with kids. Kids are eating onions like never before, simply because (as they said in the first movie) “ogres are like onions–they have layers!” Dare ya to do the same thing with creamed corn.

- A whole new category of vuvuzela emulator apps is getting lots of online buzz.

Query By Sketching

Earlier today, while Carol and I were out on an errands run, we were stopped for a light behind a beat-up pickup truck. On the back of the truck was an emblem on a sticker, and Carol asked me what it was. And in truth, I don’t know, though I’ve seen it a time or two before. It looks like a band logo, though not of any band that I’ve ever listened to.

Earlier today, while Carol and I were out on an errands run, we were stopped for a light behind a beat-up pickup truck. On the back of the truck was an emblem on a sticker, and Carol asked me what it was. And in truth, I don’t know, though I’ve seen it a time or two before. It looks like a band logo, though not of any band that I’ve ever listened to.

It was a right profile of a cartoonish man running, with his hair streaming in the wind. In one hand he’s holding a sheet of paper in front of him. The whole thing is in red, inside a red circle. There’s no text of any kind. (The figure is filled in with red; my sketch above is in red Sharpie. Also note the painfully obvious: I’m a words guy, not a pictures guy.)

The challenge intrigued me when I got home. How would I look something like that up? I tried text descriptions in Google Images: “little red guy running”, “red logo running man,” and so on. Saw lots of interesting things, but not that logo. I didn’t spend a great deal of time on it and gave up after a couple of minutes.

We don’t really have a search system for pictograms, and we probably don’t need one all that badly, but it made me wonder how we would make the attempt. Text descriptions? “Right-side profile of cartoon man running, holding a sheet of paper in front of him. Enclosed in circle. Color solid red.” Or perhaps a sort of Visio interface where we could drag across cartoon fragments of describable things and drop them into a rough sketch that the computer could compare against images in its database. This would require machine abstraction, but would be useful for identifying more than just band logos.

As with “query by humming” for music that sticks in your head, it’s a difficult problem computationally, and not as useful. My guess is we that won’t do it, not because we can’t, but because there’s no payoff. And thinking about it for a few minutes reminds me how really really far we still are from genuine “strong” AI.

In the meantime, does anybody know what the little running red guy represents?

Coding vs. Compiling EPubs

It’s always unsettling to admit that the other side has a point, but it’s good practice and often absolutely necessary. I am the VDM guy, after all, and I’ve never been one for hand-coding what can be generated automatically. As I’ve mentioned here earlier, an awful lot of people take their text and hand-code an EPub framework around it to create an ebook, which I found borderline ridiculous…until this morning. Now I think I know why they do it.

It’s simple: Our EPub compilers have a very long way to go.

The process of creating EPub-formatted ebooks can be done two ways: Write your own XML/XHTML by hand, or let a utility of some sort generate it for you. I’ve done both in recent days, and I was bowled over by the conceptual similarities between that and the gulf between writing a program entirely in assembly and writing it in an HLL like C. I’ve done a fair bit of tracing through assembly code as compiled by GCC, and I’ve been very impressed by the cleanness and comprehensibility of the assembly files it produces. GCC is one helluva compiler, as is the Delphi compiler. (And that’s where my low-level code tracing experience begins and ends, mostly.)

Well, I’ve been spoiled. Compared to GCC (or even Delphi, which is now 15 years old, egad) the EPub format is a babe in diapers: poorly understood, still growing furiously, and, as often as not, smelly as hell. All of that will pass. (I remember my nephew Brian in his diapered era; he is now 27 and an investment banker.) But in the meantime, well, the immaturity of the EPub technology must be dealt with.

I did another, larger test case EPub yesterday. I took a 15,000-word article from an old theology journal, extracted the text via ABBYY PDF Transformer, cleaned up the text (which was in fact pretty damned clean to begin with; ABBYY does a superb job here) and loaded the text into the Atlantis word processor. Without a great deal of additional editing, I exported it to an EPub file. That file may be downloaded here. (40K EPub.) There are no images, and all the text exists in a single XHTML section. It’s about as simple structurally as an EPub can get, and what you see is just as it came out of Atlantis. I did not tweak it at all post-Atlantis, neither manually nor in Sigil. (Note well that Atlantis can export EPub, but it cannot import EPub files, nor display/edit EPub XML/XHTML.) I then took that file and loaded it into Sigil, added a cover image, and split the text into two sections. You can find that file here. (1 MB EPub.) Both of these files pass EPubCheck without errors.

The Atlantis EPub renders (reasonably) well in all the local readers I have here, as well as the online Ibis Reader. It’s small (only 40K) and if you can do without a cover it’s a perfectly reasonable ebook. The Sigil copy does not do nearly as well. The online Ibis Reader refuses to render any of the images at all, including the cover image, the copyright glyph, and the generated images of the two grapevine glyphs that I inserted into the title page as decorations just to see what would happen. The copyright glyph issue is disturbing for legal reasons, but worse, it’s a standard character with a standard HTML encoding, and should be renderable irrespective of font. Ditto Azardi, which renders the Atlantis EPub well but not the Sigil copy. Over and above Azardi’s leaving out all the images (including the copyright glyph) the Sigil copy of the EPub loses what little formatting it had in the Atlantis EPub. None of the centered text remains centered, for example.

There are some additional weirdnesses in the readers themselves: FBReader renders both files well, but (weirdly) the Go Forward button moves the reading window toward the beginning of the file, and the Go Back button moves the window toward the end of the file, perfectly bass-ackwards. Ibis displays the title three times, which is overkill. FBReader handles the images just fine, but renders the copyright notice for both versions in Greek letters, sheesh.

These rendering issues are probably reader failures, since the files themselves are EPub-compliant. However, the autogenerated XML/XHTML code is often obscure, and in one case, at least, dead wrong: The title tag includes only the first line of the title. I understand that the title text is split into two lines, but I was never asked to define the text within the title tag and can only assume that Atlantis picked the first Heading 1 style it found and plugged its text into title. (The metadata for the title was stored correctly, and all readers displayed the full title text. I don’t think that the title tag is used by the readers. An empty title tag is perfectly acceptable to EPubCheck.) The gnarliest part of the compiled EPub (in both versions) is the CSS. Atlantis took the page format settings and translated them into generically named CSS classes, which are accurate representations of the word processor settings, but not easily identifiable and in no wise good quality CSS.

This isn’t insurmountable, and most of the problems I’ve had so far can be blamed on incomplete and buggy reader apps, but it shows how young a business this is. The hand coders still have the edge, and I’d be better off on the readability side creating the ebook text in a WYSIWYG HTML editor like Kompozer or Dreamweaver and hand-coding the CSS myself. That is, however, precisely what I’m trying to avoid. Sooner or later, Atlantis or something like it will offer pre-written CSS style sheets designed specifically for text intended for EPub export. That will help a great deal. In the meantime, some manual futzing is unavoidable, and my opinion of Sigil has been greatly tarnished. I may have to try something else on the EPub editor side; suggestions always welcome.

And the readers, yeech. Don’t get me started. I may have to buy an iPad just to see what my own damned books look like!

Atlantis and the EPub Toolchain

You’ve heard me say this before, and I suspect you’ll hear it again and again: Creating ebook files is much harder than it needs to be, and creating ebooks in the EPub format is particularly–and inexplicably–hard. In my June 9, 2010 entry, I spoke about the EPub format itself, and how it’s not a great deal different from a word processor file format. In fact, Eric Bowersox pointed out that OpenOffice’s ODF files are also based on XML and organized in a similar way.

Bogglingly, most people appear to be hand-coding EPub XML. In recent days I’ve been looking for better ways to create EPub ebooks. Many places online cite Sigil as the only WYSIWYG EPub editor in existence right now, and I grabbed it immediately. It’s a very nice item, but appears to be an undergraduate’s Google Code project, and I certainly hope he will hand it off to others if he ever gets tired of hammering on it. Version 0.2.1 has just been released, and it fixes a number of bugs that I stumbled over in the last couple of weeks that I’ve been using it.

Then, yesterday, without any need for ancient maps or Edgar Cayce, I found Atlantis.

The Atlantis word processor is a $35 shareware item created by a very small company in France. It’s portable software, meaning it can live on a thumb drive and does not have to be installed in the usual fashion. It’s tiny; nay, microscopic (the executable is 1.1 MB!!) and lightning fast. It doesn’t have all the fancy eye candy of modern software, but it’s amazingly capable, and highly focused on the core mission of getting documents down and formatted. It has a spellchecker and other interesting features like an “over-used words” detector. It reads and writes .doc, .docx, and .odt (ODF) files, and here’s the wild part: It exports to EPub.

Furthermore, it does a mighty good job of it. I loaded a .doc of my story “Whale Meat” into Atlantis and then exported it to EPub. The generated EPub file passed the very fussy EPubCheck validator immediately with flying colors. Now, this was pure text, without any images or embedded fonts or other fanciness, but that’s ok. You have to start somewhere, and I would prefer to start with a genuine word processor.

I then loaded the EPub file that Atlantis had generated into Sigil, which I used to divide the story into chapters and add a cover image. Sigil isn’t really a word processor in the same sense that Atlantis or Word are, but it allows split-screen editing of WYSIWYG text on one side and XML/XHTML code on the other. Sigil 0.2.0 had a bug that generated an incomplete and thus illegal IMG tag (XHTML requires the ALT attribute) but I see that the new 0.2.1 release fixes that. Adding the ALT attribute manually in Sigil 0.2.0 allowed the EPub file to pass EPubcheck without further errors.

I have not yet generated a TOC in Sigil, nor have I attempted to create an EPub of any significant size. (“Whale Meat” is only 8,700 words long.) When I’m through playing around, I’m going to load the entire .doc image of Cold Hands and Other Stories into Atlantis, export it to EPub, semanticize it in Sigil, and see what I have. At some point along the way I may be forced to hand-code (or at least hand-correct) the XML or XHTML, and you’ll hear me bellyache about it when I do. But I will admit that I’m pleased with what I have so far. Yes, Atlantis and Sigil ought to be one product, or at least two closely-knit utilities in the same product family. Still, given the primitive state of the EPub reader business (I have yet to find a Windows or Linux-based EPub reader that I’m willing to use) I’m satisfied with the way that Atlantis and Sigil cooperate. Now that Apple has anointed the EPub format for iBooks, I’m guessing that EPub-related improvements will be arriving thick and fast in coming months.