The essential difference between literary (as we define it today) and non-literary fiction didn’t crystallize for me until first-person shooters happened. I’m not one for games in general, but an hour or two playing early shooter games like Doom and Quake back in the 90s was an epiphany: This is a species of fiction. The following years proved me right. Most ambitious action games have at least a backstory of some kind, and some modern MMORPG systems have whole paperback novels distilled from them. (See Tony Gonzales’ EVE: The Empyrean Age, based on EVE Online.)

The essential difference between literary (as we define it today) and non-literary fiction didn’t crystallize for me until first-person shooters happened. I’m not one for games in general, but an hour or two playing early shooter games like Doom and Quake back in the 90s was an epiphany: This is a species of fiction. The following years proved me right. Most ambitious action games have at least a backstory of some kind, and some modern MMORPG systems have whole paperback novels distilled from them. (See Tony Gonzales’ EVE: The Empyrean Age, based on EVE Online.)

Of course it’s not literature. Did anybody say it was?

What it is is something else, something important: immersive. You get into a good game, and you’re there. I can do the same thing with a decent SF novel, but the phenomenon is in no way limited to SF. I’m guessing that Farmville or almost any reasonably detailed simulation works the same way.

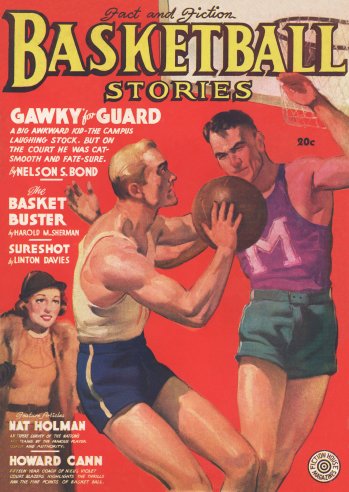

Immersivity is the continental divide between literary fiction and pulp fiction. Like anything else in the human sphere it’s a spectrum, placing World of Warcraft on one end and Finnegan’s Wake on the other, with everything else falling somewhere in the middle. The term measures the degree to which you can lose yourself in a work, where “lose yourself” means “forget that you’re reading/playing and enter into experiential flow.”

Don’t apply a value scale to immersivity. It’s only one dimension of many to be found in fiction, and my point here isn’t to dump on Finnegan’s Wake. Literature is intended to evoke a response in the reader, but that response is not necessarily immersion. (It can be, particularly with classics like Huckleberry Finn that are new enough to be culturally familiar to us–dare you to read Chaucer without footnotes!–and yet not so new as to be afraid of Virginia Woolf.)

Pulling the reader in and carrying him/her along requires a smooth, linear narrative style, a vivid setting, and enough going on to maintain the reader’s interest after a long day working a crappy job. Pulp characters are often types, but that’s not necessarily due to a lack of skill on the writer’s part. A carefully chosen and well-written type allows room for a reader to imagine being that character, which is important in immersive fiction. As much as I enjoyed Gene Wolfe’s massive Book of the New Sun (and I’ve read it three times since its publication) I had a very hard time imagining myself as Severian. I empathize with him and certainly enjoyed watching him against the dazzling surreality of Urth (though I had to read numerous sections several times to be sure I knew what was going on) but being him? No chance. Keith Laumer’s Retief, on the other hand, no problem. Louis Wu? Same deal.

And for the umptieth time: (I can hear the knives being sharpened) This is not to denigrate literary fiction, of which I’ve read a lot and still do. My point is that immersive fiction is a valid entertainment medium, requiring different mechanisms and different skills than literary fiction. Let’s not dump on things for simply being easy to read. Easy is good if easy is what you want–and (on the author side) if easy is what people are willing to pay for.

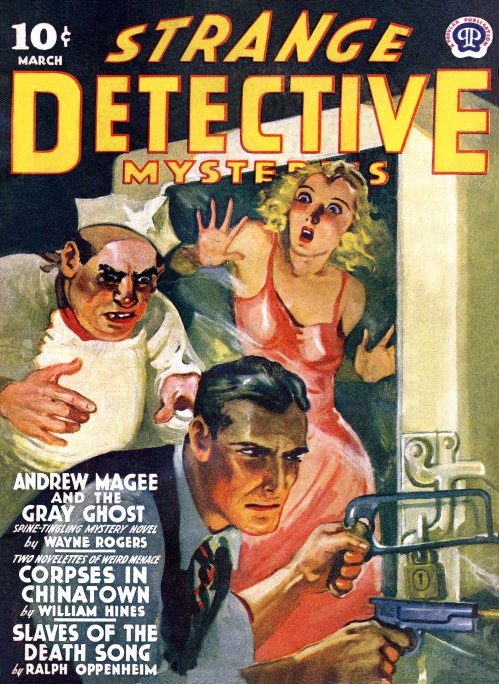

Which should not suggest that easy to read is necessarily easy to do. The immersive magic of the pulps is obscured by the fact that a lot of it was just badly done, and could not have been otherwise, given that some pulp titles paid a quarter cent a word and published eighty thousand words twice a month. We can do much better these days, at least on the quality side. A brilliant potboiler is eminently possible–if we as readers give authors some sense that it’s ok to take up the challenge, and that they’ll be paid for their efforts when they succeed.

More in this series as time allows.