- My old friend and fellow early GTer Rod Smith has posted a great many excellent pictures he took at Chicon 7, including a book signing that I attended.

- My mother’s cat Fuzzbucket died yesterday, at 16 years and change. He outlived my poor mother by twelve years, and while skittish as a kitten eventually warmed to me. I’ve never had a cat (for obvious reasons, of which I have four right now) but of all the cats I’ve never had, Fuzzbucket was my favorite. He kept his own LiveJournal page, and the final entry brought a tear to my eye.

- For those who couldn’t attend Chicon and were cut off from viewing the Hugo Awards by an idiotic copyright protection bot, you’ve got another chance: The award ceremony will be re-streamed tomorrow night, September 9, at 7 PM central time.

- This morning’s Gazette had an ad for hearing aids, which bragged of their product having 16 million transistors. This is easier than it used to be, since all those transistors are in one container. Now, does anybody remember the days when ads bragged of radios containing six transistors?

- And while we grayhairs and nohairs are recalling transistor counts in the high single digits, does anybody remember the early Sixties scandal (reported in Popular Electronics, I think) in which Japanese manufacturers would solder additional transistors into simple superhet boards and short the leads together, just so they could advertise the box as a “ten-transistor” radio?

- Nice piece from Ars Technica on the deep history of the spaceplane.

- Bill Cherepy sent a link to a marvelous steampunk tennis ball launcher, used for getting pull-strings for antennas (and as often as not, the antennas themselves) into high or otherwise inaccessible places. Gadgets like this (albeit not in steampunk dress) have been around for a long time, and I posted a link to this one (courtesy Jim Strickland) back in March.

- Also from Bill (and several others in the past few days) comes word of a promising if slightly Quixotic attempt to preserve orphaned SF and fantasy. Here’s the main site. At least they’re offering money to authors and estates; most other preservation efforts (of pulp mags and old vinyl, particularly) are pirate projects most visible on Usenet.

- That said, there are projects that limit themselves to out-of-copyright pulps, like this one. One problem, of course, is knowing when a pulp (or anything else from the 1923-1963 era) is out of copyright. Copyright ambiguity only hurts the idea of copyright. We need to codify copyright and require registration, at least for printed works. I’m not as concerned about copyright’s time period, as long as the owners of a copyright are known. As I’ve said here before, I’m apprehensive about competing with hundreds of thousands of now-orphaned books and stories.

- I don’t eat much sugar anymore, but egad, there are now candy-corn flavored Oreos.

publishing

Odd Lots

How Not to Fight Ebook Piracy

The estimable Janet Perlman recently posted a link to an article suggesting a “new” concept in ebook piracy protection that doesn’t involve any sort of encryption or tying of files to a particular device. The gist of it is to embed a purchaser’s personal information in the file purchased. If the purchaser knows his/her name or address are somewhere in the file, well, they’re less likely to post it on Pirate Bay, no?

This concept is not new; I remember talking it as long as ten years ago, when ebooks were still exotica. It’s as wrongheaded as it is obvious, for the following reason: The fastest-growing source of files shared on Bit Torrent is material taken from stolen readers, tablets, and smartphones. If somebody swipes my tablet and the files stored on it are somehow traceable to me, then once the files appear on the file sharing networks, publishers might assume that I was the one who uploaded the files–which in most cases is a felony.

This is true whether or not my name is actually embedded in the files. A serial number or database key pointing to my sales record in the publisher’s store would be enough.

I’ve written before about massive ebook collections available on pirate sites. The file I mentioned in that entry was an old one, and crude. Newer and even bigger ones are available now. (No, I won’t tell you where they are.) Specialized collections are turning up as well, as specific as books on programming for Android.

Driving the trend is the appearance of specialized private Bit Torrent trackers catering to ebooks. If you’ve never studied up on the torrent scene it’s a little hard to explain, but Big Media pressure is driving a lot of torrent traffic into a darknet of members-only trackers that keep their members on very short leashes. To avoid getting kicked out you have to upload as much as or more than you download. Of course, if nobody wants to download what you upload (because it’s of poor quality or they already have it) your ratio goes down and the admins show you the door. This creates pressure to find new material to upload, especially in private trackers with few members who very quickly grab everything of even minor interest to them.

The torrent scene is a numbers game, and ebooks are small files compared to movies or TV shows. So collection editors are grabbing files anywhere they can to spin out new collections. If your device is stolen, your files will find their way to the pirate sites. If your name (or some other identifiable traceable to you) is in those files, you’re the one in trouble, and not the pirates themselves.

File piracy may be an unsolvable problem. The last thing we want to do is propose solutions that might turn completely honest purchasers into criminals–thus providing a perverse incentive to stop buying, and pirate other people’s files instead.

The Agency Model and the Fair Trade Laws

All the recent commotion over the agency model vs the wholesale model in ebook retailing reminded me of something: my very first pocket calculator. I got my first full-time job in September of 1974, and whereas fixing Xerox machines wasn’t riches, it paid me more than washing dishes at the local hospital. In short order I got my first credit card, my first new car, and a number of other things that had been waiting for my wallet to fatten up a little.

One of these was a pocket calculator. The device itself has been gone for decades, but I’m pretty sure it was a TI SR-50, with an SRP of $149.95. I shopped around for the best price, since $150 was a lot of money back then. However, everybody who sold the SR-50 was selling it for $149.95. I bought it at a camera store downtown, and only a little research told me that it was covered under the Fair Trade laws, meaning that all retailers sold it for the same price, set by the manufacturer. I grumbled a little, but wow! I had a calculator! I gave it no further thought.

Between 1931 and 1975, a significant chunk of retailing in the United States was basically on the agency model. Books, cameras, appliances, some foods, wine and liquors, and certain other things were sold for the price the manufacturer chose. This is one reason prices were often printed right on the goods. Retailer margins were open to discussion, but in a lot of industries, the margin was 40% or pretty close to it. The Fair Trade laws were enacted during the Depression to protect local one-off retailers from being driven out of business by much larger chain stores, during a time of reduced demand and thin profits. How well this worked is disputed, but by 1975 the laws had become so unpopular with the public and so difficult to enforce that they were repealed by an act of Congress.

I grant that Fair Trade was not a clear win for the little guys. Some of my readings suggest that the Fair Trade laws accelerated the dominance of retail chains because chain retailers could build bigger stores and shelve a greater variety of goods, even if their prices were the same as prices in smaller, one-off stores. House brands were invented largely to evade the Fair Trade laws, since the retailer was considered the manufacturer for legal purposes and could set prices in stores as desired. This gave another advantage to large chains, since only large chains had the resources to establish house brands.

Fair Trade retailing as I understand it rested on two big assumptions:

- Manufacturers compete on price.

- Retailers compete on things like customer service and selection.

Shazam! Those are the same two assumptions underlying the agency model in publishing, and I don’t think it matters whether we’re talking print or digital. So I think it’s fair to look at what happened after 1975, when Fair Trade went away:

- Discounting allowed consumer prices to go down.

- Both the chains as a whole and individual chain retail stores got bigger.

- Smaller, independent stores vanished in droves.

- Small retailing became specialty retailing. This was certainly true of bookstores. Of the two bookstores I could easily reach on my bike in the 1960s, one became a card shop that carried a few books, and the other became a specialty bookstore carrying Christian/Catholic books only.

- Small retailers dealing in used goods hung on longer–think used bookstores and used record stores. The Doctrine of First Sale allowed used goods retailers to set their own prices even on Fair Trade goods.

- Manufacturer consolidation went into high gear. One reason, I think, was monopsony, which is the power big retailers have to dictate prices to suppliers. Smaller manufacturers who could not meet retailer price expectations merged with larger manufacturers, became importers, or went under.

In the ebook publishing/retailing world, #5 does not apply, as there’s no unambiguously legal used market. Most of the other consequences in the list above are things that I predict an agency model would work against:

- Retail prices will rise–though perhaps not as much as some fear.

- It will be easier to mount and maintain a new online retailer against competition by enormous retailers like Amazon.

- Given the above, with the consequence of more players in the retail market, monopsonistic pressures on cover prices will be greatly reduced.

- Absent Amazon’s monopsony, smaller publishers have a better chance of competing with much larger publishers, given small publishers’ advantages of lower fixed costs vs larger publishers.

- The presence of a larger number of smaller publishers will keep downward pressure on prices, since that’s their primary way to compete. Macmillan has to keep ebook prices up to protect its print hardcover line. Ten thousand small ebook publishers have no hardcover lines to protect. $10? No problem. $5? The new $10. Even within the agency model, small press will train consumers to expect ebooks to sell for $10 or less.

There’s another consequence that I don’t think has any precedent in the Fair Trade phenomenon: Larger numbers of retailers and publishers will reduce the power of very large retailers or publishers to “silo” the business with proprietary file standards and DRM.

There are problems with such an agency-based business model (and wildcards; Pottermore, anybody?) but overall I think those problems are more solvable than the collapse of book retailing into Amazon, Amazon, and more Amazon. So my vote goes with agency retailing. I’ve just told you why. (Polite) discussion always welcome.

Invading the Most Favored Ebook Nation

Reports are pouring in this morning that the Department of Justice is preparing antitrust action against the Big Five publishers (Simon & Schuster, Hachette, Penguin, Macmillan, and Harper Collins) and Apple for conspiring to raise ebooks prices. (It’s a little ironic that I read it in today’s print Wall Street Journal, which I generally read before turning this damned thing on.)

The problem is in part the agency model, which allows publishers to set a price for books, and give retailers like Apple and Amazon a cut. Publishers are afraid of ebooks eating their hardcover lines, of course, but were absolutely terrified that Amazon’s loss-leader pricing of bestsellers at $9.99 would train customers to think that ebooks were worth $10 and no more. Publishers have experimented with windowed release, which holds back the ebook edition until the hardcover has a chance to generate its bigger bucks, but as best I know that’s not widely done. Agency pricing, however, has stuck.

Here’s an agency example, of a hardcover I read recently: Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature has a cover price of $40. (Publishing seems to be responding to the recent shortage of ‘9’ digits by rolling prices up a penny, at least on hardcovers.) All of the ebook stores that I’ve checked are selling the ebook version for $19.99. In an agency arrangement, publishers set both prices. The sales agent (that is, the retailer) gets 30% of the set price. In this case, that would be $6. The publisher gets the rest, here $14.

Why 30%? It’s arbitrary, and simply the number that Apple gave publishers when it changed its bookstore from the wholesale model to the agency model. Apple’s retail contract had a twist, which is really what’s getting them into trouble today: The “most-favored-nation” (MFN) clause, which specifies that publishers may not give other retailers better terms than they gave Apple. Much byzantine legal reasoning online, but here’s a short summary.

TGIANAL, but this still puzzles me a little, and I think we’ll learn more in coming days. MFN clauses have been litigated and are not themselves illegal. The sense is that, if anything, they tend to drive prices down. The current legal action from Justice seems to turn on whether the Big Five colluded on agency pricing (with Apple’s help) to force Amazon to accept the same terms that Apple got. The idea is that the parties named in the suit intended their actions to raise prices, a use of MFN that is in fact illegal. If that sounds like a hard thing to prove (rather than just allege) well, duhh.

As I’ve said earlier, I favor agency pricing, because it allows small, very small, and microscopic publishers to undercut the Big Five in a major way and maybe eke out a marginal living. You can bet that you won’t see 99c ebooks from Macmillan. Much of my puzzlement arises in wondering to what extent ebook publishing will be affected by things like the Robinson-Patman Act, which was created to prevent predatory pricing, though is not widely enforced these days. When the retailer’s role in selling ebooks is basically database management (or when the retailer becomes the publisher or even the author) predatory pricing is not an issue–but odder things have happened in the legal world before.

As always with complex legal issues involving enormous players with cavernous pockets, almost anything could happen. I think the case will either be settled before going to court, or else will be decided narrowly. Publishers may be stripped of their ability to demand that retailers accept the agency model, or any given given agency percentage. I think Amazon would love to retain agency pricing, and just negotiate a lower number.

As I’ve said many times: We’re still in the Cambian era of ebooks (the Pre-Cambrian Era ended with the arrival of the Kindle) and there’s still a whole mess of evolving to do.

Indies and Gatekeepers

Janet Perlman put me on to this article about why indie publishers (a category that may or may not include self publishers, depending on whom you talk to) get no respect. The whole piece might be summed up this way:

- Quality is hard work.

- Quality is expensive.

- Quantity is no substitute for quality.

I agree, as far as it goes. But that’s not the whole story. You can break a sweat and write a superb novel at considerable expense of time and energy. You can pay an editor to look at it and perhaps fix certain things. You can pay an artist for a great cover. You can pay somebody to do a great page layout, generate print images, ebook files, and so on. Having shelled out all that expense in time, money, and personal energy, you are not likely to sell many books or become especially well-known. Publishing is an unfair business in a lot of ways.

Perhaps the most unfair thing about publishing as we know it now is that it cares not a whit about quality. Sure, the publishers will tell you otherwise. So will the agents, and so will the retailers, assuming you can find any these days. Alas, it’s not true. Publishers, agents, and retailers are indeed our gatekeepers, and the gates are tightly kept. The gates do not open for quality, alas. The gates open in the hope of making money.

This is true not only in quirky markets like fiction (more on which in a moment) but in technical publishing as well. I’ve received and rejected beautifully written books that were well-organized and basically error-free, for a simple reason: The Radish programming language (I just made that up) is used by 117 people world-wide, which means the total worldwide market for a book about Radish is 116. (The author already has a copy.) On the flipside, the best possible book on Windows XP won’t be accepted at any traditional publishing house, because all the books on XP that the universe needs were written a long time ago.

The reverse is also true, to some extent. If a publisher thinks your book will make money, the book will probably be published. Being well-written doesn’t change this equation much. Back in the Coriolis era I spent a lot of money on developmental editors to make a manuscript readable in those cases where I suspected (after market analysis) that the book met a hitherto unmet need. I wasn’t always right, of course, but the point is that I didn’t accept or reject books based on any judgment of quality. What I was looking for was market demand.

This is true of fiction as well, in spades. I picked up Cherie Priest’s steampunk entry Dreadnought last year, and had to force myself to finish it. Two other people in my circle, who live 1,000 miles apart and don’t know one another, both described the book in a single word: Unreadable. (Another said the same of her earlier book, Boneshaker.) Dreadnought was dull, slow, short on ideas, over-descriptive in some places and far too sparse in others. Yet Cherie’s got a following and is evidently doing very well. Somebody at Tor thought her books would make money and took a chance. They were right. That doesn’t make them well-written. (I did like the covers, and covers do matter–if you can get them in front of the readers somehow.)

I don’t want to be seen as picking on Cherie, who will doubtless chew me out if she reads this. It’s a pretty common thing. Nor is it a new thing. Decades ago I read a lot of abominable novels, from Sacred Locomotive Flies to Garbage World. They got into the stores. They probably made their authors at least a little money. (They got mine, after all.) They were crap.

If Dreadnought made money, why would a book that was better written not make money? It’s a long list. The author may not have been able to get a hearing from the gatekeepers in the first place. Luck is needed here, as well as brute persistence, not that persistence is any guarantee. The topic may be considered out of style, or just worked out and already done to death. It may be too long. (I ran into this trouble with The Cunning Blood. Unit manufacturing cost matters.) The book may have been judged to push buttons in the public mind that the publisher would prefer not to push. (Back when I was in high school I read a purely textual porn comedy novel that was brilliantly written and hilarious. Would I publish it? Not on your life.) Books that demean women or minorities a little too much, or focus on cruelty to animals (or probably a number of other things) won’t be picked up as easily, and it has nothing to do with quality. It’s tough to make money in publishing, and publishers are trolling for as broad a market as possible.

This is why I think the article on HuffPo cited above is misleading. Quality is a problem, but not as much of a problem as the author thinks, and not in the same ways. Worse, solving the quality problem won’t make an indie publisher’s books any more likely to get into B&N, and suggesting to indie publishers that they will is just dishonest.

So what’s the answer? Don’t know. There may not be one. The publishing industry is in the process of changing state, and nobody knows what we’ll inherit in five or ten years. Losing B&N (or waking up one day to find that B&N is a tenth the size it was yesterday) could work to indie publishing’s advantage, at least if independent bookstores fill the subsequent vacuum. The more gates to the retail channel there are, the more likely it is that one will open when you buzz. Self-published ebooks have worked for people like Amanda Hocking with Herculean energy who write for twelve hours and then promote themselves the other twelve. Tonnage can get you noticed, even if it’s bad tonnage.

For the rest of us, again, I don’t know. Quality in all writing (fiction especially) is not the choke point. It’s an unfair and beneath it all a mysterious business. Submit good work if you can, but be prepared to have the gates shut in your face a lot. That’s just what gates do.

Odd Lots

- You’re getting two Odd Lotses in a row for a reason. Stay tuned–I’ll try and explain tomorrow, if I don’t run out of Aleve.

- Bruce Eckel is returning his Kindle Fire because the damned thing will not render .mobi files. C’mon, Amazon. I mean, come on. (Thanks to Mike Bentley for the link.)

- Xoom 2, where are you? Whoops, it’s going to be called the Droid XYboard to distance itself from the Xoom brand, which was done in because Somebody Didn’t Want It To Have a Card Slot. (Don’t know who. Have suspicions.)

- Charlie Stross makes a good case that DRM on ebooks (as required by the Big Six) is a stick handed to Amazon with which to pummel the Big Six. Read the piece, follow the links (make sure you know what a “monopsony” is) and then read the comments.

- Schumann resonance waves can apparently be detected from space. This is surprising, as my earlier readings suggested that they only exist by virtue of a sort of immaterial waveguide formed by layers in the Earth’s atmosphere–the same waveguide effect that allows hams like me to bounce signals around the world.

- Femtotech? I postulated a “femtoscope” in my novel The Cunning Blood, but it was used to plot quantum pair creation and did not rely on exotic matter. I’m not sure such things are possible, or could be done in any environment where we could live or even work through proxies. But as with a lot of things (especially LENR) I would hugely enjoy being wrong.

- I torrented down the brand-new Linux Mint 12 Lisa the other day, and like its predecessor it will not detect the video hardware correctly on my 2009-era Core 2 Quad with NVidia 630i integrated graphics. Somewhat surprisingly, it will install on an older Dell GX620 USFF with (as best I can tell) no video problems. Not sure if I like GNOME 3, though. MATE, a GNOME 2 fork, has promise.

- I may have made this point once before, but hard steampunk authors should have the Lindsay Books catalog on hand, or at least have the site bookmarked. These are books explaining how to actually do steampunk technology, often in the form of reprints of original Victorian-era reference texts. Thermite, brass, steam engines, and loads of other goodies just as great-great grandpa learned them. (Thanks to Bruce Baker for the noodge.)

- One of my German friends told me that plagiarism in German doctoral theses is so widespread that it’s spawned a crowdsourced mechanism for detecting it. That’s the abbreviated English-language version; if you have a reasonable amount of German, go to the richer, fuller main page.

- Very spooky time-lapse video of a little-known physical phenomenon. (Thanks to Pete Albrecht for the link.)

- I originally thought this was a hoax. On the other hand, I have a Tim Bird and I love it. It’s hard to believe that such things actually work as well as they do.

- Sometimes you wear what you eat–or at least a reasonable facsimile.

Pirates and Dummies

I used to go up to the Pirate Bay on an almost weekly basis, to see which Paraglyph Press books were listed there. It ceased to be a priority after Paraglyph folded, and I don’t think I’ve been up there for over a year. Then last week I learned that large NY publisher John Wiley & Sons is preparing a multiple “John Doe” style lawsuit focused on torrent piracy of its staggeringly popular “For Dummies” series. So I sailed back up to the Bay to see how bad it is on the ebook side.

For dummies in search of “For Dummies,” my initial impression is that it’s pretty good, which means that for Wiley, it’s pretty bad. The word “Dummies” can be found in TPB’s torrent catalog 691 times, and although some of those may not be “For Dummies” titles, I’m guessing that nearly all of them are. Individual books are listed, of course, but what probably worries publishers more is that a 6.3 GB file containing 572 “For Dummies” books is listed as well. 6.3 GB sounds like a lot. It’s not. It’s about the size of a single 720p feature-length Blu-Ray rip. 572 PDF ebooks in one lump, egad–in truth, I didn’t know that there were that many “For Dummies” books in existence. (GURPS for Dummies is not something I would have gone looking for.)

Alas, the pirates have forgotten about me personally, and for that matter, about Paraglyph Press itself. Only one Coriolis book is listed, Michael Abrash’s Graphics Programming Black Book. (There may be others that weren’t cited with the word “Coriolis;” I didn’t search deeply.) As I said, my own last name isn’t present even once. Much more startlingly, David Brin is listed only three times. Connie Willis, twice. Vernor Vinge, once. Nancy Kress, not at all. Being hot must help; Neil Gaiman is listed 49 times.

One gets the impression that reading isn’t a priority among pirates. To find out just what is, you need a better metric, and The Pirate Bay offers one: the number of complete torrents. “Seeders” are people who make available complete copies of a given file. “Leechers” are those who are currently downloading the file. The more seeders, the more popular a file, and the faster it will download to the leechers. (The protocol is interesting and described well here.)

Although there are hundreds of torrent trackers, the Pirate Bay is by far the most popular, ranking 91 on Alexa. I think it’s pretty characteristic of the pirate world in general. So let’s go count Pirate Bay seeders:

- The top audio book is Double Your Reading Speed in Ten Minutes. 548 seeders. (Irony alert! Near-toxic levels!)

- The top ebook is Do Not Open: An Encyclopedia of The World’s Best-Kept Secrets. 1,442 seeders.

- The top pirated app is Photoshop CS5. 6,412 seeders.

- The top music track is “We Found Love” by Rihanna. 7,010 seeders.

- The top game is The Elder Scrolls. 12,438 seeders.

- The top movie is Conan the Barbarian. 17,422 seeders.

- The top TV show (in fact, the top torrent of any kind) is an episode of “How I Met Your Mother.” 23,259 seeders.

I hope I don’t have to beat you over the head with it: Video is twenty times more popular on torrent sites than ebooks. Down in Dummies land, it’s worse: The 572-book “For Dummies” collection has all of 99 seeders. Neil Gaiman’s best (46) is less than half of that.

So why is a major book publisher suing a relative handful of torrenters? I’m guessing that it’s because it can. BitTorrent is extremely “open” in terms of who’s doing it, and if you’re downloading you’re automatically uploading too. Recording the IPs of people in a torrent swarm is easy. Suing them is dirt simple. Some money can be harvested offering settlements, but at those minuscule usage levels, not much. I’m sure that Wiley wants to exert a “chilling effect” on sharing of Dummies books, and they are–but only in the torrent world. Even though my books vanished from the Pirate Bay, it didn’t take Sherlock Holmes to find them out on the bitlockers and Usenet, which for various reasons are much tougher nuts to crack on the legal side.

Video rules the torrent world because video is big, and the BitTorrent protocol is the most effective way to get video downloaded quickly. Small files like ebooks are elsewhere, unless they’re gathered into massive collections the size of Blu-Ray rips. Ebook piracy seems to be a minor issue today because ebook piracy is mostly invisible. It’s out there, and for all that I’ve pondered the problem, I return to the conclusion that the problem has no solution other than to sell the goods easily and cheaply, and to stop teaching people to be pirates by making the media experience complicated with DRM.

In the meantime, announcing mass lawsuits of torrenters of a specific product line pulls the Streisand chain hard. You might as well yell “Come and get it!” to people who hadn’t known that all 572 Dummies books (or ebooks generally) could be found on torrent sites. This has to be balanced against whatever chilling effect the lawsuits may have, and I can’t help but think that it’s a wash, at best. The real result of such suits over the years has been to push piracy into places where it’s difficult to see and almost impossible to police. The First Principle of whatever we try has to be this: Don’t make the problem worse. If this means that no solution presents itself, we may have to content ourselves with that.

Hephaestus Books and Deceptive Titles

Here’s an emerging story, first pointed out to me by Bruce Baker: There’s a new POD business out there selling free content that isn’t quite what it appears to be. A firm called Hephaestus Books in Richardson, Texas is listing literally hundreds of thousands of POD titles (166,000, as of this morning) on the major online booksellers, including Amazon, B&N, and BooksAMillion. Some are familiar public domain material. Some of them are eye-crossing minutiae that maybe seventeen people in the world would find interesting. Some sound scholarly. (Here’s an example.) But many of the newest sound like compendia of popular modern novels that in no way are in the public domain, like Jerry Pournelle’s CoDominium stories. And for $13.85, yet.

Sounds like. And here’s the catch: The POD books in question do not contain the novels listed in the title.

That would be difficult, considering that most of the books from Hephaestus are 40-80 pages long. They in fact contain discussion about the novels, much of it harvested from Wikipedia, all of it shoveled (presumably by scripts) into a file accessible by POD print machinery. Most of the big-name writers in SF are represented in the Hephaestus catalog, including Larry Niven, David Brin, and Charlie Stross, but lots of far more obscure names are there, too, like Robin Hobb. Check for yourself: Go to Amazon’s search page and type the name of any (reasonably) well-known writer, followed by “Hephaestus.” Prepare to be surprised–after all, there are 166,000 books to choose from. (Alas, don’t look for me. Already checked.)

So what precisely is this? Copyright infringement? Given the scorched-earth penalties called out by the DCMA, I doubt there’s any infringing material in these books. They’d be nuts to do that. Some online have suggested that this might be a legal issue called “tort of misappropriation” of a celebrity’s publicity rights (which, interestingly, are very well protected by Texas law) but I myself don’t think so. There are strong fair-use protections of discussion and criticism of events, things, and people, and a lot of redistributable content online. This seems to be what Hephaestus is selling. If they trip up, it’s likely to be on consumer-protection grounds, since the titles of many of these books are very deceptive. It’s a tough thing to prove, though, and the whole business seems to have been constructed with considerable skill.

One thing I still don’t understand is the cost of the ISBNs. Every book I’ve seen has an ISBN, and the ISBNs appear to be legitimate. ISBNs are not free, and in fact cost about a dollar each, even in blocks of 1,000. Given that the vast majority of these books are never likely to be ordered, even once, the burden falls on the rest to make back the investment in ISBNs given to all of them. ISBN’s for 166,000 books must have cost them about $150,000. That’s a hefty upfront cost for a revenue stream as dicey and unpredictable as this one.

How much they’re making per book is impossible to tell without knowing more about how they’re being distributed. Ingram and similar companies charge fees for mounting POD books on their systems, which would send the upfront cost for the press hurtling into the millions dollars–before they sell a single book. I’m still looking into this, but it’s a head-scratcher first-class. If you know anything more than I’ve summarized here, please pass it along.

Ah, well. This is only the latest emergence of a phenomenon that’s been with us for some time. I call such presses “shovelshops.” The big retailers could kill them in an hour by restricting the speed with which titles can be registered. Even presses like Wiley and Macmillan don’t publish more than a handful of books per day. The Hephaestus business model depends upon thousands upon thousands of books appearing very quickly. If no press can register more than ten or twenty books a day, it’ll take a long time to get the title count to the point where the number of clueless customers begins to pay off.

And then there’s always that sleepy dragon, the FTC, which may or may not be prodded enough to take notice. In the meantime, buy nothing from Hephaestus Press. You’ll be glad you didn’t.

Sixteen Inches in Seven Books

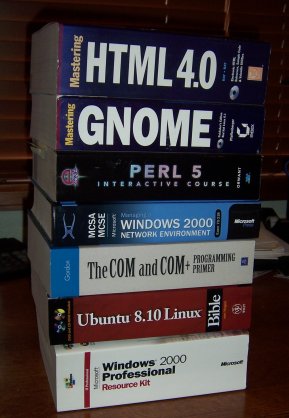

Space is getting tight in here again, and books are getting tossed on top of other books. It’s long past time to thin the ranks a little–both on the shelves and in the closet–and in standing in front of the computer section here it occurred to me that if I were attempting to free up shelf-inches I should probably go after the biggest spines first.

Space is getting tight in here again, and books are getting tossed on top of other books. It’s long past time to thin the ranks a little–both on the shelves and in the closet–and in standing in front of the computer section here it occurred to me that if I were attempting to free up shelf-inches I should probably go after the biggest spines first.

And so I did. After no more than five minutes, I freed up sixteen inches of shelf space–in seven books. None of these are essential. I have other, much newer books on HTML and GNOME, and given that I haven’t written a line of Perl in five years or more, one Perl book (out of two) is plenty. There is no longer a single instance of Windows 2000 here beyond a VM, so monster Win2K tomes are doing nothing but crowding out other, more useful things from my shelves.

Speaking of which: The top two titles date back to the mid-1990s, and illustrate the “spine wars” raging at the time among computer book publishers. If your books were all three inches thick, there would be fewer shelf-inches in the bookstores for your competitors, so we all wanted to make ours three inches thick. (Sybex was a champ at that, as you can see.) Coriolis published a few thick books, the thickest of which was Michael Abrash’s Graphics Programming Black Book, but compared to the other presses we were pikers. Huge spines tended to crack and spill pages in regular use, as we discovered after Michael’s book was out there for awhile. Page count was not always in proportion to spine width, either. Mastering HTML 4.0 was barely 1,000 pages long. The Coriolis HTML Black Book by Steve Holzner (2000) was 1,200 pages long, and only 1 5/8″ thick. That’s 200 more pages in one fewer inch. The difference was thicker, pulpier paper.

The Microsoft Press book at the bottom is a sort of circus freak and may never be equalled in the spine wars: It’s 1,800 pages long and a full 3″ thick. It’s not a bad book, but I’ve wondered here before it it was mostly a stunt.

Anyway. I’ve already culled an additional six or seven books, but I doubt I will ever have a stack equalling the one shown above. Ahh, computer book publishing in the spine-swellin’ 90s–what a ride that was!

Taos Toolbox 2011, Part 2

(Part 1 here.) The Snow Bear Inn is really a set of ski condos only a quarter mile from one of the Taos Ski Valley lifts. The units are complete apartments including kitchens, some with single bedrooms, some with two. Jim Strickland and I shared a two-bedroom suite. The kitchen was well-equipped; indeed, far better equipped than we needed. It had a separate wine refrigerator, coffee grinder, four-slot toaster, blender, crockpot, and probably a few other things on the high shelf that we never poked at. Food was provided in the common room for tinker-it-up breakfasts and lunches. Four dinners a week were catered in by a local woman who really knew her stuff.

Jim and I quickly fell into a daily routine: I’d be up at 6, showered by 6:15, and shoveling grounds into the coffee maker by 6:30. Jim got up about then, and I’d scramble two eggs for each of us. By 7:30 we were already hard at work unless someone stopped by for coffee, as Nancy Kress did more than once. (See above.) But even with morning visitors, by 8:30 both of us were reading mail and hammering out notes on the manuscripts up for critique later that day.

By 10:00 we were gathered around the conference table in the common area downstairs, and if anybody wasn’t there by precisely 10, Walter would lean out the door and give a blast on the Air Horn of Summoning. This happened rarely; mostly we were all present and ready to roar by 9:45. On most days work began with a lecture by Nancy, followed by a short break and then either two or three stories for critique. Lunch happened as time allowed, often before the third critique but always limited to thirty minutes. The class day wrapped up with a lecture from Walter. At that point, typically between two and three PM, we would shift into edit mode, and begin work on the following day’s critiques and our own second-week submissions. Some worked in the common room. Most of us went back to our own rooms. (Alan Smale preferred to sit with his laptop on a folding chair between the buildings.)

I quickly fell back into college-student mode, taking notes on a quad pad in my frenetic block printing, precisely as I did at DePaul in 1974. By Tuesday July 12 we were definitely into drink-from-the-firehose mode, critiquing first-wave submissions (distributed via email before the workshop began) that ran as long as 11,000 words. Toward midweek we were also working hard on our second-week submissions, which nominally demonstrated what we’d learned in the first few days.

Dinner was catered in at 6PM every day but Friday. While not exotic, the fare was beautifully prepared, and included barbecued ribs, coconut shrimp, broiled tilapia, grilled steaks, baked chicken breast, home-made potato & egg salad, and lots of other things I may have been too tapped-out mentally to recall. There was always good conversation over dinner (see above: Peter Charron and Ed Rosick) but by 6:45 most of us to our scattered laptops went, continuing work for the following day. I sometimes kept hammering until 8 or 8:30. At that point I was toast and generally gave Carol a call before falling exhausted into bed. There was a little late-night fellowship over bottles of wine down in the common room, but it all happened long after my bedtime.

Some people managed to get the 20-odd miles down the valley to Taos for occasional shopping or touristing, but my old bones preferred to stay put and rest while rest was possible. The impression I want to give here is that this was boggling hard work, and unlike my Clarion experience back in 1973, there was almost no clowning around.

My camera doesn’t do a great job with indoor shots. For a good collection of captured moments from the workshop, see Christie Yant’s Flicker album.

Next: How critiquing worked.